Forthcoming is such a lovely word.

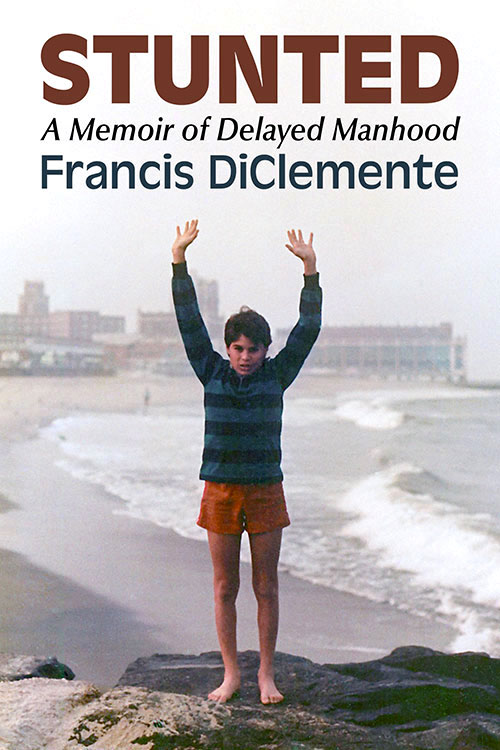

And I’m happy to share the cover image for my coming-of-age memoir, Stunted: A Memoir of Delayed Manhood, which is slated to be published later this year. It was a long, hard road to get here, but I am honored that the story has found a home with Toplight Books, an imprint of McFarland & Company.

Cover image for my memoir.

The book is also listed on Amazon, Bookshop, and Goodreads.

I began researching this project in June 2013 after marrying my wife, Pam, who has been a steadfast supporter, cheering me on along the way. I obtained medical records dating back to 1984 and incorporated journal entries from the early 1990s. So in many ways, I’ve been writing this memoir my whole life. The impetus to write the book sprang from a long blog post I wrote in December 2014 to mark the 30th anniversary of my initial brain surgery at SUNY Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, New York.

At Walt Disney World in 1985, a few months after my initial brain surgery.

When I started working on the memoir, I realized I needed to study the genre, so I read the classics like Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr, This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff, Running with Scissors by Augusten Burroughs, Wild by Cheryl Strayed, Stop-Time by Frank Conroy, Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, and many, many others.

Between that initial blog post and the completion of the book, life intruded.

I had two brain surgeries, was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, mourned the loss of my stepfather, Bill Ruane, my Uncle Fiore DeCosty (nicknamed Fee), and two cousins, Derek and Damon DeCosty. I published numerous poetry collections, wrote a play that was produced by a small theater in Las Vegas, produced a few documentary films, and earned two Emmy awards. I bought a house (reluctantly), and most importantly, became a father to my son, Colin, who will be ten years old next month and was diagnosed with autism in 2018.

The whole time I was living my life in the present while my head remained partly stuck in the time period from 1984 to 1995, covering the terrain of my high school experience in Rome, New York, my undergraduate years at St. John Fisher College (now named St. John Fisher University), in Rochester, New York, graduate school at American University in Washington, DC, and the start of my professional career back in my hometown of Rome and in Venice, Florida.

Here’s me in either my junior or senior year of high school or my freshman year at St. John Fisher College in Rochester, New York.

And as time elapsed and I wondered if I would ever finish the book, I drafted scenes, wrote a crappy first draft, completed multiple revisions on my own, and then hired developmental and line editors through Fiverr, wrote a book proposal, and sent out countless queries to agents and publishers who accept direct submissions from authors.

While I am ecstatic that the book will be published, I detest the necessity of the promotional phase. But it’s a reality I can’t escape. My intention is for readers to find some universal truth or connection to my personal story.

Here is the book description from the McFarland site.

Set between 1984 and the mid–1990s, this coming-of-age memoir follows Francis DiClemente’s experience of adolescence and early adulthood in a body that struggled to develop. Diagnosed with a rare brain tumor that led to hypopituitarism, DiClemente remained physically underdeveloped while his peers matured into young adulthood. As he navigated relationships and sexuality in college, it became evident that his prolonged experience with physical nonconformity fueled isolation, self-doubt, and shame.

This book explores the impacts of his condition on schooling, intimacy, and emerging adulthood, examining how physical differences shape identity formation. It reframes masculinity not as a function of physical development, but as an ethical and emotional practice grounded in empathy, resilience, and responsibility. Contributing to conversations on embodiment and self-acceptance, the work offers insight into the experience of living at odds with normative timelines of growth and belonging.

And I was very fortunate to have some gifted and generous writers provide blurbs for marketing.

“Francis DiClemente’s searingly honest memoir offers a vital perspective for anyone grappling with their own place in the world.”

—Shivaji Das, author of The Visible Invisibles

“Francis DiClemente and I met as teenagers on a baseball diamond in the summer of 1983, and while I have since gone on to work in a different sport populated by alpha males gifted with superhuman size, strength, and athleticism, I know of no better or stronger example of what manhood truly means than my friend. This moving story of self-discovery, which Francis courageously tells with raw honesty and vulnerability, reminds us that the journey toward fulfillment in life is inward, and should inspire us to be less judgmental—not only of others but ourselves.”

—Bob Socci, broadcaster, New England Patriots

“DiClemente’s journey becomes a lifelong battle, man against regrowing tumor. In these pages, he provides the most intimate details of how he learned to be a man while trapped in the body of a boy. Hopefully, his words, and his honesty, can reassure other boys and men grappling with masculine identity.”

—Angel Ackerman, author of the Fashion and Fiends horror series and founder of Parisian Phoenix Publishing

“This is a deeply moving testament to the quiet courage it takes to claim your identity in a world that insists on defining it for you. For anyone who has ever felt unseen or out of place, DiClemente offers a reimagined vision of identity rooted not in the body, but in the soul.”

—Brittany Terwilliger, author of The Insatiables

“Francis DiClemente has written a book on men and masculinity that should be not only savored but consulted by those men who, at some point in their lives, have questioned what their manhood means and what place it holds in society. And by those men I mean all men. This work might have been born of DiClemente’s many masculine hardships, but it becomes a celebration of what is best in us.”

—William Giraldi, author of The Hero’s Body

“DiClemente delivers an unflinching account of the brain tumor that disrupted normal growth and his participation in one of the first human growth hormone trials. …a touching and compelling memoir.”

—Carmen Amato, author of the Galliano Club historical fiction series

“Francis DiClemente tells it like it is—with no BS. This work is honest, human, and full of hope. I respect the courage it took to write it.”

—William Soldato, author of Under Too Long

“Francis DiClemente’s book is a courageous and beautifully crafted memoir that speaks to the quiet battles so many face in silence. With poetic clarity, brutal honesty, and emotional depth, he explores identity, masculinity, and the long road to self-acceptance. A powerful book.”

—Apple An, award-winning author of Las Crosses, Mother of Red Mountains, and Daughter of Blue City

I’m now working on a second book, which is a continuation of the story. There’s no timetable for completion.

One note about the cover.

My Uncle Fiore took my photo in 1985 at the New Jersey shore. We had traveled to New Jersey from Rome one early fall weekend to visit my cousin, Fiore, who was stationed at an Army prep school in Monmouth County, where he would spend a year before matriculating to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. I remember listening to Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A. album on my yellow Sony Walkman in the backseat on the way down from Rome to Jersey. I connected the song “I’m Goin’ Down” with our southbound travel, and I loved side two of the album, especially the songs “No Surrender,” “Bobby Jean,” and “My Hometown.”