I wanted to share that poet Michael Anthony Ingram has highlighted me for his Quintessential Poetry Spotlight. The post includes a PDF with some sample poems.

I wanted to share that poet Michael Anthony Ingram has highlighted me for his Quintessential Poetry Spotlight. The post includes a PDF with some sample poems.

Here are some poems for Valentine’s Day. They were culled from previous collections and were written when I was still single and living in Phoenix, Arizona. I added some photos I took during that time period (1998-2006).

Heart Sunlight. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

Solo V-Day

There is no love without another,

no romance when no companion is present.

The self cannot survive on its own.

Affection needs an outlet,

a target to these romantic thoughts.

And happiness demands reciprocation,

because desire withers when forced to remain inside,

and love has no point when Cupid’s bow fails to strike.

Morning on Fairmount Avenue. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

An Involuntary Condition

Here’s to all those whose

birthday wishes never came true—

for the unloved, unlucky and desperate,

for the manic and passive,

for the childless Demeter searching

in vain for her unborn Persephone,

for the clones of Sisyphus rolling

the stones of their loneliness,

groaning under the weight,

straining in the face of repeated defeat.

For the wedding days when

you will not stand upon the altar,

for the groves of family trees

shriveled and lacking offspring.

For all the men and women

who hate being single

and rebel against it every day,

but can do nothing to prevent

becoming orphans in their adulthood.

Slanting Desert Tree. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

Nightingale

I have worshipped at the

altar of loneliness for far too long.

I need a love intervention—

a woman, an angel, a friend,

a nightingale to swoop in on my life

and replace the discordant, recurring song.

Late Afternoon Light. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

Roommates

My pursuit of a union has ended,

And the desire to keep looking is gone,

Dissolved like Kool-Aid

Crystals in cold water.

I no longer fear the inevitable,

Because it already resides here.

I accept the reality of my adult life:

Loneliness is my only mate,

A discarnate presence

Occupying my twin bed at night.

Overnight Stay

The unattached go unnoticed

in hotel bars and lobbies,

watching couples and

overhearing conversations.

They retreat to their rooms

and fall asleep to the

sound of cable television,

turning up the volume

before drifting off

in order to shut out

the animal noises of

the man and woman

enjoying themselves

in the adjacent room—

while being reminded again

that others are not

spending the night alone.

Sunlight on Chair. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

Saturday Night at the Cinema

Couples hurry down the aisle

of a movie theater,

finding seats as the house lights dim

and the previews start.

Locked in a state of solitude,

I gaze at them with envy.

For I remain alone . . .

a single ticket purchased,

no fingers entwined in a warm lap,

no shared overpriced soda or tub of popcorn,

no arm around her shoulder,

pushing aside her long brown hair.

But I am able to forget my life

while the sprockets are engaged.

The shuttering picture seduces me again,

and I become numb to everything—

until the last frame passes,

when knowledge of my isolation

rumbles like a stagecoach procession

across the Arizona desert

in a John Ford Western.

Then the film noir,

black and white feeling returns.

And as the end credits roll,

I stand up and flee

the darkness of the theater,

stepping into the artificial light

of the shopping mall parking lot.

Left-Hand Fetish

With regard to women,

I am obsessed with one body part.

If I spot a woman I like

seated in a crowded café,

or walking through an airport,

my eyes travel directly

to the top of her left hand.

I need to know right away:

Does she wear an engagement ring

or wedding band?

Is she free to love me,

if she so chooses?

Or is she already partnered

with another man?

The Look

I noticed that look—

that look that

she was looking

at him instead of me.

I was neither cast aside,

nor dismissed outright,

but much worse—

completely overlooked.

Hurtful Words

The voice of a woman

I admire from afar

pierces the afternoon air.

Her voice mingles

with other sounds

inside the lobby

of the Phoenix Art Museum

on a Saturday in February.

The woman does not

intend to be cruel.

Yet she crushes my heart,

dispersing romantic hope,

when she delivers

a simple sentence,

beginning with the words:

“My boyfriend is . . .”

She proceeds to tell a co-worker

about her weekend plans,

but I stop listening,

as I realize

there’s no point

to knowing more.

I was leafing through a hefty stack of unpublished poems in my home office yesterday, and this one struck me. I think the you referenced in the poem is actually me—so I need to heed my own advice.

May You Live

May you come to the realization

That you have no control.

May you relinquish your desire

To dictate the path of your existence.

May you surrender to the absurdity

Of this exercise in futility,

Understanding that this beautiful mess

Known as life will lead you

where it wants you to go. No exceptions.

May you realize that death is rushing toward you,

And it’s coming for all of us.

May you realize that your family and friends

Will be unable to spare you from this fate.

Why do I pester you with these dark thoughts?

Simply so you’ll pause to appreciate the few moments

We are granted on the surface of this earth.

The chance to mix and mingle

And touch and caress with flesh and spirit.

The opportunity to laugh and love and interact

before disease and illness and old age

Make us weary of carrying around

A body that will soon be a corpse.

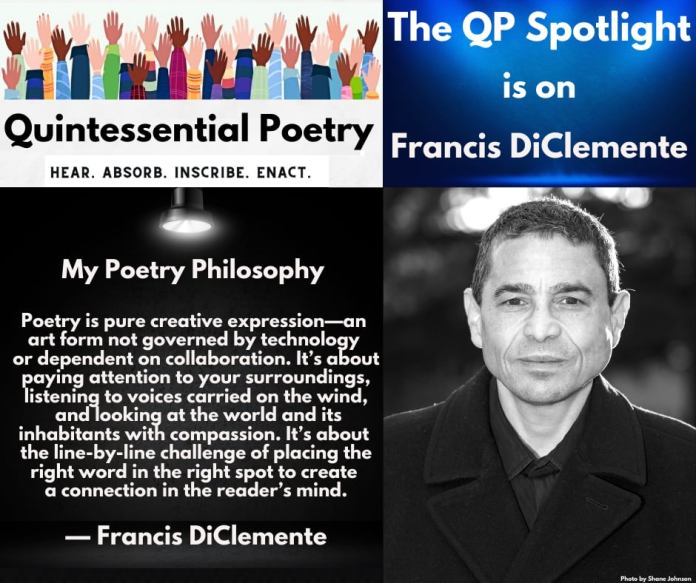

Forthcoming is such a lovely word.

And I’m happy to share the cover image for my coming-of-age memoir, Stunted: A Memoir of Delayed Manhood, which is slated to be published later this year. It was a long, hard road to get here, but I am honored that the story has found a home with Toplight Books, an imprint of McFarland & Company.

Cover image for my memoir.

The book is also listed on Amazon, Bookshop, and Goodreads.

I began researching this project in June 2013 after marrying my wife, Pam, who has been a steadfast supporter, cheering me on along the way. I obtained medical records dating back to 1984 and incorporated journal entries from the early 1990s. So in many ways, I’ve been writing this memoir my whole life. The impetus to write the book sprang from a long blog post I wrote in December 2014 to mark the 30th anniversary of my initial brain surgery at SUNY Upstate Medical University Hospital in Syracuse, New York.

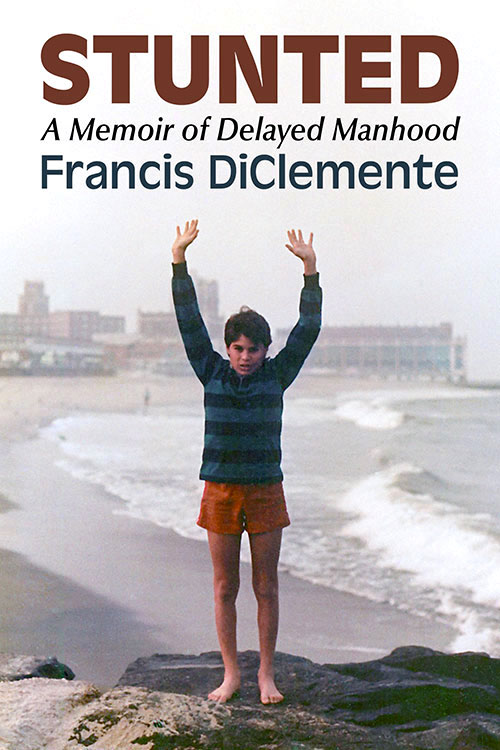

At Walt Disney World in 1985, a few months after my initial brain surgery.

When I started working on the memoir, I realized I needed to study the genre, so I read the classics like Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr, This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff, Running with Scissors by Augusten Burroughs, Wild by Cheryl Strayed, Stop-Time by Frank Conroy, Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, and many, many others.

Between that initial blog post and the completion of the book, life intruded.

I had two brain surgeries, was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, mourned the loss of my stepfather, Bill Ruane, my Uncle Fiore DeCosty (nicknamed Fee), and two cousins, Derek and Damon DeCosty. I published numerous poetry collections, wrote a play that was produced by a small theater in Las Vegas, produced a few documentary films, and earned two Emmy awards. I bought a house (reluctantly), and most importantly, became a father to my son, Colin, who will be ten years old next month and was diagnosed with autism in 2018.

The whole time I was living my life in the present while my head remained partly stuck in the time period from 1984 to 1995, covering the terrain of my high school experience in Rome, New York, my undergraduate years at St. John Fisher College (now named St. John Fisher University), in Rochester, New York, graduate school at American University in Washington, DC, and the start of my professional career back in my hometown of Rome and in Venice, Florida.

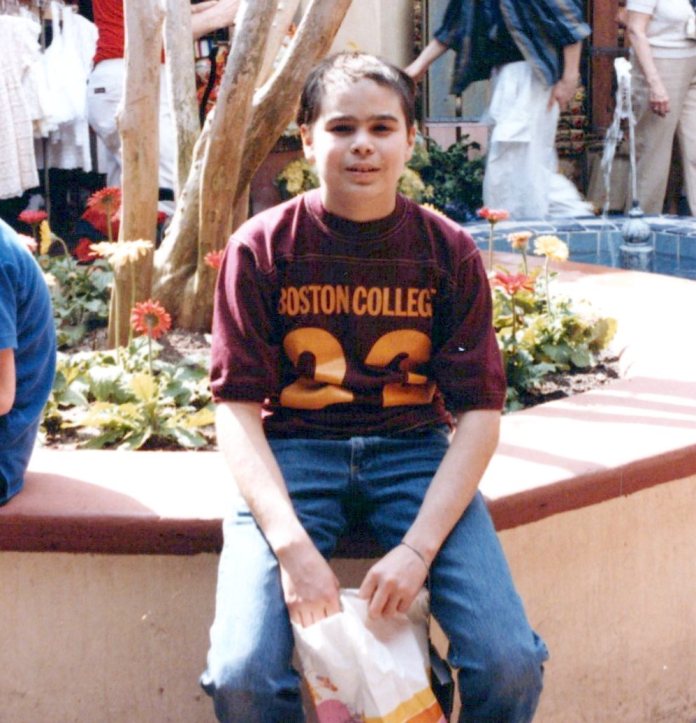

Here’s me in either my junior or senior year of high school or my freshman year at St. John Fisher College in Rochester, New York.

And as time elapsed and I wondered if I would ever finish the book, I drafted scenes, wrote a crappy first draft, completed multiple revisions on my own, and then hired developmental and line editors through Fiverr, wrote a book proposal, and sent out countless queries to agents and publishers who accept direct submissions from authors.

While I am ecstatic that the book will be published, I detest the necessity of the promotional phase. But it’s a reality I can’t escape. My intention is for readers to find some universal truth or connection to my personal story.

Here is the book description from the McFarland site.

Set between 1984 and the mid–1990s, this coming-of-age memoir follows Francis DiClemente’s experience of adolescence and early adulthood in a body that struggled to develop. Diagnosed with a rare brain tumor that led to hypopituitarism, DiClemente remained physically underdeveloped while his peers matured into young adulthood. As he navigated relationships and sexuality in college, it became evident that his prolonged experience with physical nonconformity fueled isolation, self-doubt, and shame.

This book explores the impacts of his condition on schooling, intimacy, and emerging adulthood, examining how physical differences shape identity formation. It reframes masculinity not as a function of physical development, but as an ethical and emotional practice grounded in empathy, resilience, and responsibility. Contributing to conversations on embodiment and self-acceptance, the work offers insight into the experience of living at odds with normative timelines of growth and belonging.

And I was very fortunate to have some gifted and generous writers provide blurbs for marketing.

“Francis DiClemente’s searingly honest memoir offers a vital perspective for anyone grappling with their own place in the world.”

—Shivaji Das, author of The Visible Invisibles

“Francis DiClemente and I met as teenagers on a baseball diamond in the summer of 1983, and while I have since gone on to work in a different sport populated by alpha males gifted with superhuman size, strength, and athleticism, I know of no better or stronger example of what manhood truly means than my friend. This moving story of self-discovery, which Francis courageously tells with raw honesty and vulnerability, reminds us that the journey toward fulfillment in life is inward, and should inspire us to be less judgmental—not only of others but ourselves.”

—Bob Socci, broadcaster, New England Patriots

“DiClemente’s journey becomes a lifelong battle, man against regrowing tumor. In these pages, he provides the most intimate details of how he learned to be a man while trapped in the body of a boy. Hopefully, his words, and his honesty, can reassure other boys and men grappling with masculine identity.”

—Angel Ackerman, author of the Fashion and Fiends horror series and founder of Parisian Phoenix Publishing

“This is a deeply moving testament to the quiet courage it takes to claim your identity in a world that insists on defining it for you. For anyone who has ever felt unseen or out of place, DiClemente offers a reimagined vision of identity rooted not in the body, but in the soul.”

—Brittany Terwilliger, author of The Insatiables

“Francis DiClemente has written a book on men and masculinity that should be not only savored but consulted by those men who, at some point in their lives, have questioned what their manhood means and what place it holds in society. And by those men I mean all men. This work might have been born of DiClemente’s many masculine hardships, but it becomes a celebration of what is best in us.”

—William Giraldi, author of The Hero’s Body

“DiClemente delivers an unflinching account of the brain tumor that disrupted normal growth and his participation in one of the first human growth hormone trials. …a touching and compelling memoir.”

—Carmen Amato, author of the Galliano Club historical fiction series

“Francis DiClemente tells it like it is—with no BS. This work is honest, human, and full of hope. I respect the courage it took to write it.”

—William Soldato, author of Under Too Long

“Francis DiClemente’s book is a courageous and beautifully crafted memoir that speaks to the quiet battles so many face in silence. With poetic clarity, brutal honesty, and emotional depth, he explores identity, masculinity, and the long road to self-acceptance. A powerful book.”

—Apple An, award-winning author of Las Crosses, Mother of Red Mountains, and Daughter of Blue City

I’m now working on a second book, which is a continuation of the story. There’s no timetable for completion.

One note about the cover.

My Uncle Fiore took my photo in 1985 at the New Jersey shore. We had traveled to New Jersey from Rome one early fall weekend to visit my cousin, Fiore, who was stationed at an Army prep school in Monmouth County, where he would spend a year before matriculating to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. I remember listening to Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the U.S.A. album on my yellow Sony Walkman in the backseat on the way down from Rome to Jersey. I connected the song “I’m Goin’ Down” with our southbound travel, and I loved side two of the album, especially the songs “No Surrender,” “Bobby Jean,” and “My Hometown.”

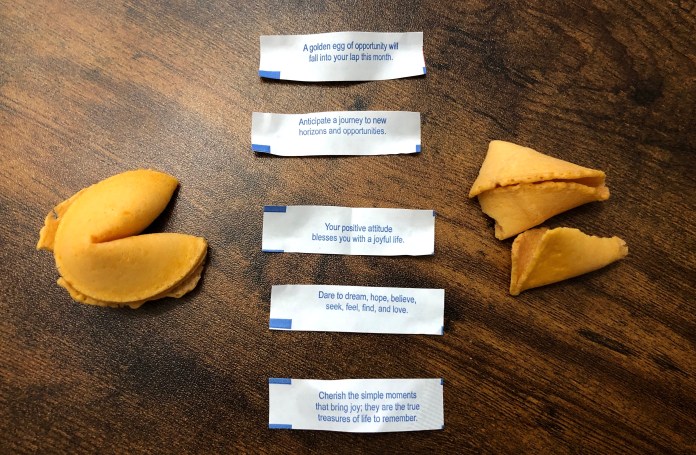

My wife bought a bag of fortune cookies at the Asian Food Market in Syracuse. So lately I’ve been grabbing the cookies and cracking them open to reveal what wisdom the universe is sending my way. But this feels like cheating—like you should only be granted one fortune cookie with a single order of Chinese food (maybe once a month).

But it’s been fun for my wife and me to compare our fortunes on a nightly basis. And I like to edit the text that the cookies spit out.

Here are some recent fortunes and revisions tinctured with my inherent pessimism:

One:

A golden egg of opportunity will fall into your lap this month.

A steaming pile of you know what will fall on your head this month (likely in the form of something broken or needing repair at our house).

Two:

Anticipate a journey to new horizons and opportunities.

Anticipate a journey to new horizons and opportunities (in bed).

Anticipate a journey to nowhere new—just more of the same in the form of the daily grind.

Three:

Your positive attitude blesses you with a joyful life.

Your negative attitude shields you from the inexorable suckiness of life.

Four:

Dare to dream, hope, believe, seek, feel, find, and love.

Boy, do I love the intention of this fortune. It reminds me of a quote which is apparently falsely attributed to Mark Twain:

“Twenty years from now, you will be more disappointed by the things you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.”

My twist:

Yes, do all those things: Dare to dream, hope, believe, seek, feel, find, and love.

At the same time, however, accept the likelihood of failure, recognizing that your dreams and desires may never come true.

Five:

Cherish the simple moments that bring joy; they are the true treasures of life to remember.

This one is perfect, and I won’t sully it with my dark interpretation. I do believe simple, mundane moments can deliver tiny bursts of joy. For me, it’s hugging and kissing my son or finding inner peace when reflecting in nature.

Plastic bag in tree.

Bag in the Breeze

Thursday morning, 9:47 a.m.

White airy clouds

painted against a pale blue sky.

Whipping sounds like

baseball cards spinning in bicycle spokes

call out to pedestrians

moving on the salt-crusted sidewalk.

A medical helicopter zips overhead.

You look up as it flies out of sight.

And with your head still raised,

you spot a plastic shopping bag

tangled on a leafless branch,

stuck at the top of a tree,

flapping in the breeze.

The bag waves its white flag

in an overture of surrender,

hinting at submission to the grip of winter,

while struggling to break loose,

straining to be released,

and waiting for a new wind to set it free.

©2017 Francis DiClemente

(Sidewalk Stories, Kelsay Books)

Winter sunrise. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

On Leaving Syracuse

The grass may not

be greener elsewhere,

but at least

it won’t be

covered with snow.

My son, Colin, stomping in the snow while waiting for the bus. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

This poem is pure fiction, but it arose out of a parent’s fear of losing a child.

Sitting by the Fire in Winter

I sit with my grief.

I wrap it around myself

like an overcoat,

while staring at the

embers of the fire,

holding my dead son’s

ski jacket close to my nose,

and remembering his

cold, little hands,

wet socks,

and the smell of his

sweaty head in winter.

During a recent appointment at the Nappi Wellness Institute at SUNY Upstate Medical University Hospital, I saw this impressive mural by Japanese artist Tomokazu Matsuyama.

Solitude Aqua Amore, 2023 by Tomokazu Matsuyama.

I’ve written about the soothing effect of hospital art before. A few years ago, a framed print in an MRI waiting room inspired this poem, which was published in my 2021 collection, Outward Arrangements: Poems.

Waiting with Vincent

A scheduled MRI

of the brain shifts

my thoughts toward

all of the

“what if, worst-case scenarios.”

While waiting for my name

to be called,

I see a print of Irises (1889)

hanging on a wall.

From far across the room,

without my glasses,

the slanted vertical

green leaves

look like snakes

writhing in the dirt.

But the longer

I stare at the image,

the calmer I feel.

Placid is the word

that comes to mind.

And I’m thankful Vincent

spends a few

moments with me

prior to my appointment

with the tube machine.

Because when sitting

in a hospital

waiting room,

artwork by Vincent

never fails to lift the spirits.

A van Gogh painting beats

People magazine

or an iPhone screen

every time.

The mural is entitled Solitude Aqua Amore, 2023, and Matsuyama worked with the nonprofit organization RxART, which “pairs leading contemporary artists with pediatric hospitals to develop site-specific projects that humanize the healthcare environment and improve the patient experience.”

I think it’s a wonderful concept, and I have no doubt that colorful artwork in hospitals lifts the spirits of little patients and their parents during their tense moments (or hours) of testing, waiting, and meeting with doctors and medical staff.

The RxART website displays images of completed projects at hospitals across the country.

I like the close-up iPhone photo I took because it put me smack in the middle of the painting, and the detailed image made me think of a Jackson Pollock drip painting—but featuring birds.

Detail image of Solitude Aqua Amore, 2023.

Here is the wall text for Matsuyama’s piece:

Tomokazu Matsuyama

Solitude Aqua Amore, 2023

Courtesy of the Artist

“Tomokazu Matsuyama is a contemporary artist who is keenly aware of the nomadic diaspora, a community of wandering people who seek to understand their place in a world of contrasting visual and cultural dialects. Tomokazu has created this bright and uplifting imagery to transform the institute’s International department. This work, inspired by “a thousand origami cranes,” encapsulates the essence of hope, peace, and the mythical attributes of good fortune. Utilizing geometric forms and organic curves, he weaves the inherent desire associated with the ‘senbazuru’ tradition into a narrative that resonates with the contemporary era. Tomokazu was born in Takayama, Gifu, Japan, and lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. RxART is grateful to Chris Salgardo, ATWATER, and Ducati for lead support of this project.”

Side note: These days, it seems whenever I read biographical text about a writer, poet, filmmaker, or artist, the bio invariably ends . . . “[Insert artist name] lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.” And that makes me wonder if poems are flying through the air and paint is flowing in the streets of Brooklyn. If I ever get to New York again, I’ll need to make my way there to explore the scene.

I want to wish everyone a Happy New Year. I’m not going to list an inventory of accomplishments (or lack thereof) from 2025 or state any intended resolutions for 2026.

Instead, I will take the day to rest up after shoveling snow in the wake of a massive storm that walloped Central New York.

And I will also share a poem I recently read in The Essential Poems by Jim Harrison.

It seems fitting for New Year’s Eve, as does one of my previous poems about the essence of time (below). I love the line about “my imperishable stupidity,” since I can relate.

Calendar

Back in the blue chair in front of the green studio

another year has passed, or so they say, but calendars lie.

They’re a kind of cosmic business machine like

their cousin clocks but break down at inopportune times.

Fifty years ago I learned to jump off the calendar

but I kept getting drawn back on for reasons

of greed and my imperishable stupidity.

Of late I’ve escaped those fatal squares

with their razor-sharp numbers for longer and longer.

I had to become the moving water I already am,

falling back into the human shape in order

not to frighten my children, grandchildren, dogs and friends.

Our old cat doesn’t care. He laps the water where my face used to be.

Harrison, Jim. Jim Harrison: The Essential Poems. Edited by Joseph Bednarik, Copper Canyon Press, 2019.

Clock on the Wall

Time is an entity unconcerned

With our hopes and aspirations.

It marches on unimpeded,

Multiplying seconds to minutes

And making centuries.

It is unswayed by emotions

And unaffected by our wishes and ambitions.

It is heartless in its swiftness—

A thief and a robber,

And life’s only true survivor.

It is unmerciful in its lack of discretion,

And unstoppable in its one-way direction.

It does not yield, it never ends and

It does not ask us our permission.

And yet, we still ask it for more.

Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems by Francis DiClemente (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

No revelation, poem, story, or promotion here. I just want to take a moment to say Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays to everyone. Thanks for reading the blog throughout the year, and I look forward to catching up with readers and my fellow bloggers in 2026.

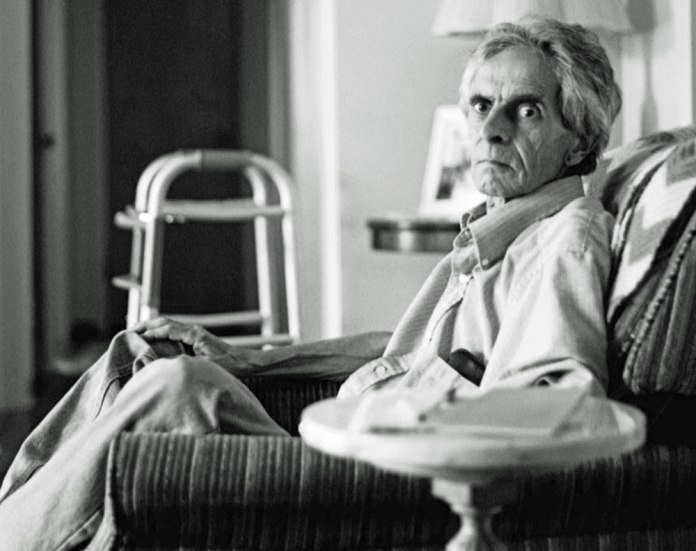

Today marks the birthday of my late father, who passed away from lung cancer at the age of 64 in August of 2007. This post was first published in 2016 and has been revised slightly. Francis DiClemente Sr. was a quiet man who led a solitary life.

My late father, Francis DiClemente Sr.

He put in 32 years at the Sears Roebuck store in Rome, New York, before the company decided to close it in the early 1990s. He rose to the ranks of a sales manager after starting his employment in his late teens, and he served in all departments: electronics, home improvement, heating and cooling, paints, and even the automotive center.

The Sears store in Rome in 1993. Photo by John Clifford/Daily Sentinel.

One of my childhood thrills was visiting him at the store after school, as we would descend a flight of stairs into a warehouse in the basement—filled with washers and dryers, lawnmowers, rolls of carpet, and other merchandise. We would go into the break room, and he would buy me a soda from the glass vending machine—usually Nehi grape, root beer, or Dr. Pepper—and then pour a cup of coffee for himself. We’d sit and talk at a little round table covered with the latest edition of the Utica Observer-Dispatch or the Rome Daily Sentinel newspaper.

Things I recall about him:

His lupine face with dark, searching eyes, bushy eyebrows and thick, black hair.

Being a devoted player of the New York Lottery. He scored some jackpots on occasion, including one that totaled more than a thousand dollars. But the scant prizes could never make up for what he spent on a daily basis.

After he died, I went through his room to clean out things, and I discovered innumerable losing lottery tickets stuffed inside one of his dresser drawers. I couldn’t understand why he would save tickets that held zero value. Was he trying to run the numbers through some elaborate mathematical system in order to calculate a winning combination, some key to unlock the mystery of how to beat the odds?

Being a habitual gambler with a penchant for playing football parlays. But his real joy came from betting the horses at the local OTB, sharing camaraderie with other men infected with the same urges, all of them standing around scribbling in the margins of the Daily Racing Form.

After the Sears store closed, he took a low-paying sales job at a carpet store. He complained about the crumbling upstate New York economy and grumbled about his bad luck, repeating the phrase, “I can never catch a break.” Even so, he endured his situation and became a valued employee at the store—one who was highly regarded for treating customers well and giving them deals whenever he could.

When he was diagnosed with cancer, the doctor told him he could try chemotherapy, but it would only give him a slim chance of living slightly longer. He decided against the treatment, noting, “What’s the point?” And so in February of 2007, he stoically accepted his fate, knowing he had only about six to nine months left to live.

Dad in his chair. It’s out of focus, but I love how he looks directly at the camera. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

I had recently relocated to Central New York from Arizona, and I was fortunate enough to spend a lot of time with him before he passed.

He lived with his mother, my grandmother Amelia, a stooped, red-haired woman who had coddled my father from the early days of his youth. He clung to her as the anchor of his life, which contributed to the demise of my parents’ marriage and also affected our relationship.

My late grandmother, Amelia DiClemente.

I don’t fault my grandmother because I don’t think she could have helped herself when it came to trying to protect my dad. He had been born with a hole in his heart, and the life-threatening condition worsened as he grew. He was a short, frail, and underweight boy who was mocked by other kids about his size, labeled as a “shrimp.”

In the late 1950s, my grandparents took my father to Minneapolis, where pioneering heart surgeon C. Walton Lillehei repaired the ventricular septal defect in a seven-and-a-half-hour operation at the University of Minnesota Heart Hospital.

And Dad was proud to have been among the first batch of patients to survive open-heart surgery in the U.S. Whenever he told the story to someone, he would lift up his shirt and show off the long scar snaking down the middle of his chest.

His medical history inspired this short poem:

Open Heart

My father was born

with a hole in his heart,

and although repaired,

nothing in his life,

ever filled it up.

The defect remained,

despite the surgeon’s work—

a void, a place I could never touch.

Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

##

As the months passed in the spring and early summer of 2007, he became weaker and weaker as the cancer ate away at his body, leaving him looking like a shriveled scarecrow.

He had always eschewed desserts and when offered them, would say, “No. I hate sweets.” But as his time on earth elapsed, he went all out when it came to food—eating Klondike bars, Little Debbie snacks, Hostess cupcakes, and other junk food. His philosophy was “Why not?”

Although he had Medicaid, Dad left behind a staggering amount of unpaid medical bills. But what troubles me more, what I have been unable to reconcile, is how he ran up thousands of dollars in debt in the last few months of his life, the largest chunk coming from ATM cash withdrawals using my grandmother’s credit card.

I was never able to pin down how he spent the money. He made no large purchases of electronics or home furnishings. I assumed he used the money to gamble; but in some way I wish he had supported a mistress or a family he never told us about, or that he gave away the cash to charities. Instead, I am only left with unanswerable questions. I helped him to file for bankruptcy, but in an ironic turn to the story, he died before a decision was reached in the case.

Dad, side angle. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

I remember a funny conversation I had with him one afternoon while we sat in the living room of my grandmother’s small ranch house in north Rome. Sunlight poured through a large bay window, past the partially opened silk curtains. Outside I could see a clear sky and trees burgeoning with leaves—a bright, saturated landscape of blue and green.

I sat in a corner of the room and he sat in a forest-green recliner covered with worn upholstery.

“What’s the name of the angel of death?” he asked me.

I was surprised by the question, and I said, “I think he’s just called the angel of death.”

“No, he has another name,” he said.

And after a few seconds it came to me. “The Grim Reaper.”

“That’s right, that’s it,” he said.

“Why do you want to know?” I asked. “Did you see him in a dream or something?

“No, but I want to know his name when he comes.”

That conversation sparked an idea for a full-length play, entitled Awaiting the Reaper. I could go on and on about my dad, but that’s the strongest memory I have of him in his waning days.

Dad in the kitchen. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

Dad never earned prestigious academic honors, never published a book, never ran a company or made enough money in his lifetime to buy a retirement home in Florida.

Instead, he toiled away in obscurity and mediocrity as a working-class person. My sister and I received no inheritance, save a small insurance policy that paid out after his death. And his shy, aloof nature created a buffer with other people, a barrier to forming deep relationships (except with a few close friends).

A photo of my father and me following my Confirmation in 1984.

Yet in reviewing his life, I know his kindness, work ethic, and willingness to help others set an example for me that I have tried to uphold. And the debts he accrued do not cancel out those qualities.

The one word I keep coming back to is decency. My father was a good and decent man. That may not be cause for celebration in our society. But it’s enough to fill me with pride, and I hope to carry on his values as I carry on his name.

I’ll close this post with two poems. The second one also mentions my late mother, Carmella.

The Galliano Club

From street-level sunlight to cavernous darkness,

then down a few steps and you enter The Galliano Club.

Cigar smoke wafts in the air above a cramped poker table.

Scoopy, Fat Pat and Jules are stationed there,

along with Dominic, who monitors it all,

pacing pensively with fingers clasped behind his back.

A pool of red wine spilled on the glossy cherry wood bar,

matches the hue of blood splattered on the bathroom wall.

A cracked crucifix and an Italian flag loom above,

as luck is coaxed into the club with a roll of dice

and a sign of the cross.

Pepperoni and provolone are piled high for Tony’s boys,

who man the five phone lines

and scrawl point spreads on thick yellow legal pads.

Bocce balls collide as profanity whirls about . . .

and in between tosses, players brag about

cooking calamari (pronounced “calamad”).

Each Sunday during football season,

after St. John’s noon Mass,

my father strolls across East Dominick Street

and places his bets,

catapulting his hopes on the shoulder pads of

Bears, Bills, Packers and Giants.

His teams never cover

and he’s grown accustomed to losing . . .

as everything in Rome, New York exacts a toll,

paid in working class weariness and three feet of snow.

But once inside The Galliano, he feels right at home,

recalling his heritage, playing cards with his friends.

And here he’s no longer alone,

as all have stories of chronic defeat.

Blown parlays, slashed pensions

and wives sleeping around,

constitute the cries of small-town men

who have long given up on their out-of-reach dreams.

For now, they savor the moment—

a winning over/under ticket, a sip of Sambuca

and Sunday afternoons shared in a place all their own.

Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

Vestiges

My parents are gone.

They walk the earth no more,

both succumbing to lung cancer,

both cremated and turned to ash.

With each passing year,

their images become more turbid in my mind,

as if their faces are shielded

by expanding gray-black clouds.

I try to retain what I remember—

my father’s deep-set, dark eyes and aquiline nose,

my mother’s small head bowed in thought or prayer

while smoking a cigarette in the kitchen.

I search for their eyes

in the constellations of the night sky.

I listen for their voices in the wind.

Is that Rite Aid plastic bag snapping in the breeze

the voice of my father whispering,

letting me know he’s still around . . .

somewhere . . . over there?

Does the squawking crow

perched in the leafless maple tree

carry the voice of my mother,

admonishing me for wearing a stained sweater?

Resorting to a dangerous habit,

I use people and objects as “stand-ins”

for my mother and father,

seeking in these replacements

some aspect of my parents’ identities.

A sloping, two-story duplex with cracked green paint

embodies the spirit of my father saddled with debt,

playing the lottery, hoping for one big payoff.

I want to climb up the porch steps and ring the doorbell,

if only to discover who resides there.

In a grocery store aisle on a Saturday night

I spot an older woman

standing in front of a row of Duncan Hines cake mixes.

With her short frame, dark hair, and glasses,

she casts a similar appearance to my mother.

She is scanning the labels,

perhaps looking for a new flavor,

maybe Apple Caramel, Red Velvet, or Lemon Supreme,

just something different to bake

as a surprise for her husband.

A feeling strikes me and

I wish to claim her as my “fill-in” mother.

I long to reach out to this stranger in the store,

fighting the compulsion

to place a hand on her shoulder

and tell her how much I miss her.

I fear that if my parents disappear

from my consciousness,

then I too will become invisible.

And the reality of a finite lifespan sets in,

as I calculate how many years I have left.

But I realize I am torturing myself

with this twisted personification game.

I must remember my parents are dead

and possess no spark of the living.

And I can no longer enslave them in my mind,

or try to resurrect them in other earthly forms.

I have to let them go.

I have to dismiss the need for physical ties,

while holding on to the memories they left behind.

And so on the night I see the woman

in the grocery store aisle,

I do not speak to her,

and she does not notice me lurking nearby.

But as I walk away from her,

I cannot resist the impulse to turn around

and look at her one last time—

just to make sure

my mother’s “double” is still standing there.

I want her to lift her head and smile at me,

but she never diverts her eyes

from the boxes of cake mixes lining the shelf.

Sidewalk Stories (Kelsay Books, 2017)