This essay first appeared in the Spring/Summer 2015 issue of South 85 Journal, an online literary magazine.

##

I once used the N-word as a weapon to achieve a goal.

It happened when I was in fifth or sixth grade at DeWitt Clinton elementary school in my hometown of Rome, New York. During recess on a cool, sunny day in early spring, I started playing a game called “Catch the Fly” with my friend Mike. The shouts of kids congregating on the school grounds mingled to form a cacophony. Weeds, broken bottles, and scattered bubble gum and Now and Later candy wrappers lined a chain-link fence that separated the schoolyard from an alley.

In the game, two players took turns throwing a tennis ball or a squishy pink ball against the brick facade of the school building. The person throwing the ball acted as a hitter in baseball. The goal was for the fielder to make three outs and retire the side, while the thrower tried to get the ball past the fielder and thus move imaginary runners around the imaginary bases.

I was playing the field, and Mike tossed the ball against the building. I can’t remember if it was a pop fly or a grounder, but as I raced to catch the ball, Cassie Donaldson (name changed), a tall, Black girl, stole it from me. She either snagged the ball in midair or retrieved it after it skirted by me toward the chain-link fence.

School building. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

“Hey, give it back,” I yelled to Cassie. No recess monitors or adults were stationed outside to enforce fair play. Cassie looked at me while standing a few feet away. She flashed a smile, almost begging me to give chase. And so, I did.

I took off and rushed after her as she bolted, cutting through a crowd of kids gathered in the middle of the schoolyard. Her long legs pumped with fluid motion, and she outran me easily.

It’s worth mentioning that she was one of the fastest and most athletic students in our class. She beat most of the boys in the 50 and 100-yard dashes timed in gym class, and she was often one of the first players chosen by captains when dividing teams for kickball or soccer games.

As the chase continued, Cassie circled the building, running on the sidewalk along Ann Street. She opened a wide gap as I pursued her. We were then alone near the front of the school. She was galloping away, and the futility of the chase became obvious. My short legs failed me; I grew tired and gave up.

After I stopped running, my eyes focused on her back, and her figure appeared smaller with every passing second. I recall she was wearing a long-sleeve green shirt. I caught my breath and screamed, “Give it back, you N-word.”

She broke stride, pulling up instantly. She did not turn around; instead, she hurled the ball over her shoulder and walked away, heading in the same direction she had been running.

The ball bounced toward me, and I picked it up. I walked back to the schoolyard with a tightness building in my stomach. By now, Mike had found some other kids to play with, but once he saw I had the ball, we picked up where we left off.

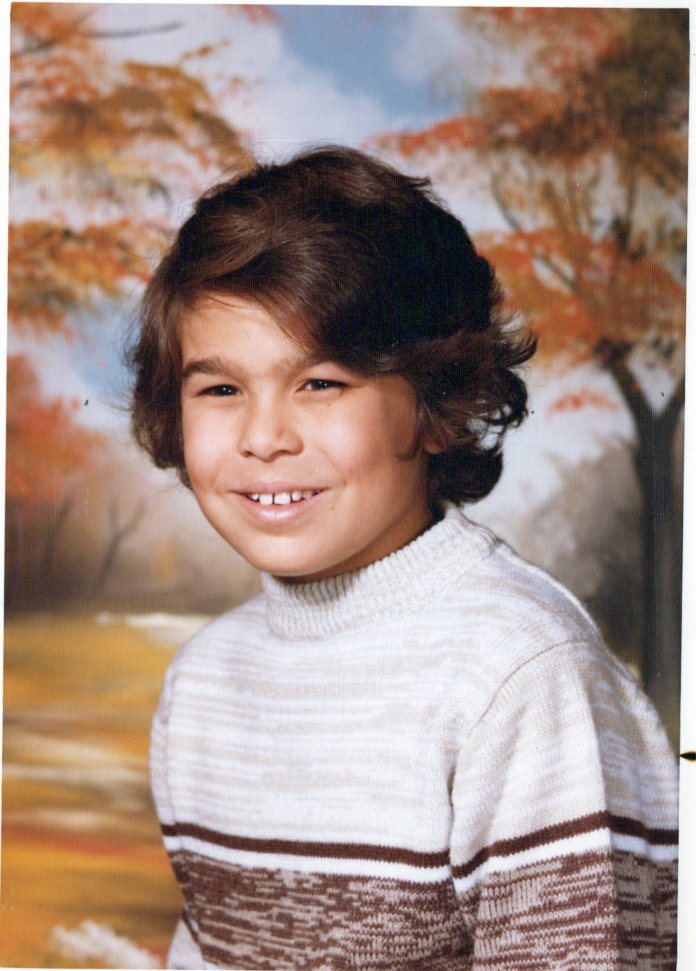

Playing third base in youth league baseball in Rome, New York, in the late 1970s.

But I lost my enthusiasm for the game. And while I felt vindicated because Cassie had taken the ball without provocation, I knew what I said was wrong and had stung her. Yet despite the viciousness of the N-word, its usage had produced the desired result: I had reclaimed possession of my ball.

I had learned the N-word from my father. He used it on occasion when complaining about some of the residents in our city or when watching sports on television.

I know he had a racist disposition. But at times, race seemed to matter little to him. Some of his co-workers at the Sears store where he worked were Black, and I remember he enjoyed chatting and joking with them. He also knew Cassie’s parents, and he would stop to talk to them if we saw them at school or in the grocery store. He also used to give them good discounts on kitchen, electrical, and hardware products at Sears.

So why did he use the N-word? I think it became a habit for him, and I made the mistake of emulating his bad behavior.

Even so, I considered myself colorblind in elementary school. Some of my friends at DeWitt Clinton were Black, and I had grown accustomed to playing sports with Black kids in Rome. Race did not seem like an issue to us.

Yet when I felt humiliated on the school grounds, I had yelled the insult without thinking about who I was targeting.

I must have apologized to Cassie at some point because we remained friends all the way through high school. But I don’t remember what I said to her or the circumstances surrounding the mea culpa. Most likely, I would have apologized to Cassie either before class resumed that day or later on the bus ride home. Or maybe I never told her how sorry I was for what I had done. Maybe we carried our unspoken knowledge of the incident with us as we climbed the grades in school.

And I faced no repercussions. I was not called to the principal’s office to explain my actions, nor was I confronted by my parents after school. And not being punished made me feel even guiltier about my behavior.

It would have been easy for Cassie to squeal on me. We lived on the same street as the Donaldsons on a rural road in South Rome. Her parents could have stopped by our house after work that night and shared the news with my parents.

I often wondered why Cassie never told anyone what I said (or at least I believe she didn’t). Maybe she thought, what good could come from telling her parents one of her classmates had called her a racial slur at recess? What could be gained from it except making her mother and father feel anger and heartache over the treatment of their daughter?

But I had gained something. I learned about the power of words and their impact on others. I discovered how one racial epithet could imbue a girl with shame, altering her body language and stopping her from running freely on a sidewalk.

I can’t say for sure that I never used the N-word again or that it hasn’t popped into my head on occasion. But from that day forward, I don’t remember ever speaking it aloud or directing it at anyone. And I realize racism cannot be cured in one passing swoop. We must struggle every day to reject the baser tendencies of our personalities.

Fortunately, Cassie never held a grudge against me for my childhood misconduct. And I never forgot her or the lesson she taught me in the schoolyard on a spring day in the early 1980s.