Today marks the birthday of my late father, who passed away from lung cancer at the age of 64 in August of 2007. This post was first published in 2016 and has been revised slightly. Francis DiClemente Sr. was a quiet man who led a solitary life.

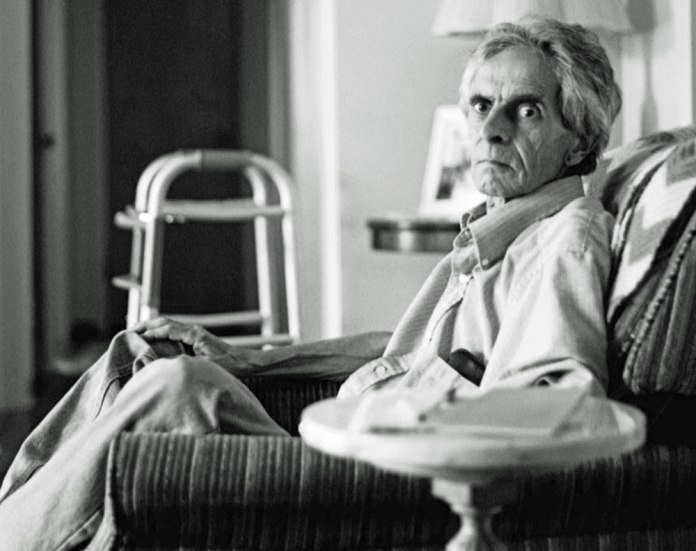

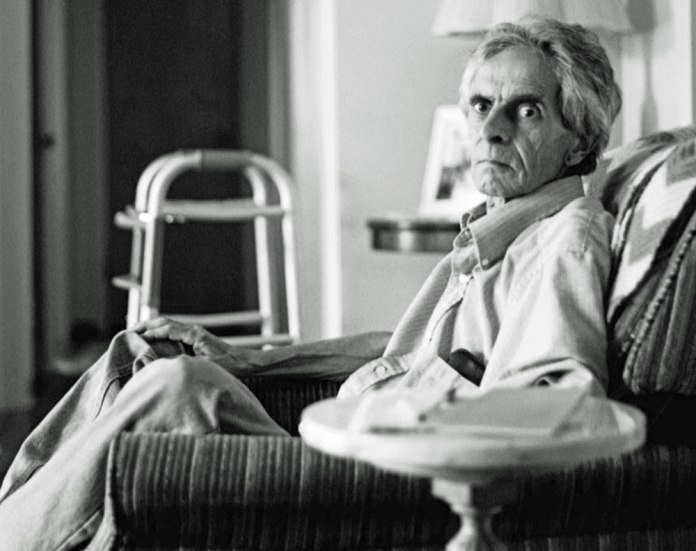

My late father, Francis DiClemente Sr.

He put in 32 years at the Sears Roebuck store in Rome, New York, before the company decided to close it in the early 1990s. He rose to the ranks of a sales manager after starting his employment in his late teens, and he served in all departments: electronics, home improvement, heating and cooling, paints, and even the automotive center.

The Sears store in Rome in 1993. Photo by John Clifford/Daily Sentinel.

One of my childhood thrills was visiting him at the store after school, as we would descend a flight of stairs into a warehouse in the basement—filled with washers and dryers, lawnmowers, rolls of carpet, and other merchandise. We would go into the break room, and he would buy me a soda from the glass vending machine—usually Nehi grape, root beer, or Dr. Pepper—and then pour a cup of coffee for himself. We’d sit and talk at a little round table covered with the latest edition of the Utica Observer-Dispatch or the Rome Daily Sentinel newspaper.

Things I recall about him:

His lupine face with dark, searching eyes, bushy eyebrows and thick, black hair.

Being a devoted player of the New York Lottery. He scored some jackpots on occasion, including one that totaled more than a thousand dollars. But the scant prizes could never make up for what he spent on a daily basis.

After he died, I went through his room to clean out things, and I discovered innumerable losing lottery tickets stuffed inside one of his dresser drawers. I couldn’t understand why he would save tickets that held zero value. Was he trying to run the numbers through some elaborate mathematical system in order to calculate a winning combination, some key to unlock the mystery of how to beat the odds?

Being a habitual gambler with a penchant for playing football parlays. But his real joy came from betting the horses at the local OTB, sharing camaraderie with other men infected with the same urges, all of them standing around scribbling in the margins of the Daily Racing Form.

After the Sears store closed, he took a low-paying sales job at a carpet store. He complained about the crumbling upstate New York economy and grumbled about his bad luck, repeating the phrase, “I can never catch a break.” Even so, he endured his situation and became a valued employee at the store—one who was highly regarded for treating customers well and giving them deals whenever he could.

When he was diagnosed with cancer, the doctor told him he could try chemotherapy, but it would only give him a slim chance of living slightly longer. He decided against the treatment, noting, “What’s the point?” And so in February of 2007, he stoically accepted his fate, knowing he had only about six to nine months left to live.

Dad in his chair. It’s out of focus, but I love how he looks directly at the camera. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

I had recently relocated to Central New York from Arizona, and I was fortunate enough to spend a lot of time with him before he passed.

He lived with his mother, my grandmother Amelia, a stooped, red-haired woman who had coddled my father from the early days of his youth. He clung to her as the anchor of his life, which contributed to the demise of my parents’ marriage and also affected our relationship.

My late grandmother, Amelia DiClemente.

I don’t fault my grandmother because I don’t think she could have helped herself when it came to trying to protect my dad. He had been born with a hole in his heart, and the life-threatening condition worsened as he grew. He was a short, frail, and underweight boy who was mocked by other kids about his size, labeled as a “shrimp.”

In the late 1950s, my grandparents took my father to Minneapolis, where pioneering heart surgeon C. Walton Lillehei repaired the ventricular septal defect in a seven-and-a-half-hour operation at the University of Minnesota Heart Hospital.

And Dad was proud to have been among the first batch of patients to survive open-heart surgery in the U.S. Whenever he told the story to someone, he would lift up his shirt and show off the long scar snaking down the middle of his chest.

His medical history inspired this short poem:

Open Heart

My father was born

with a hole in his heart,

and although repaired,

nothing in his life,

ever filled it up.

The defect remained,

despite the surgeon’s work—

a void, a place I could never touch.

Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

##

As the months passed in the spring and early summer of 2007, he became weaker and weaker as the cancer ate away at his body, leaving him looking like a shriveled scarecrow.

He had always eschewed desserts and when offered them, would say, “No. I hate sweets.” But as his time on earth elapsed, he went all out when it came to food—eating Klondike bars, Little Debbie snacks, Hostess cupcakes, and other junk food. His philosophy was “Why not?”

Although he had Medicaid, Dad left behind a staggering amount of unpaid medical bills. But what troubles me more, what I have been unable to reconcile, is how he ran up thousands of dollars in debt in the last few months of his life, the largest chunk coming from ATM cash withdrawals using my grandmother’s credit card.

I was never able to pin down how he spent the money. He made no large purchases of electronics or home furnishings. I assumed he used the money to gamble; but in some way I wish he had supported a mistress or a family he never told us about, or that he gave away the cash to charities. Instead, I am only left with unanswerable questions. I helped him to file for bankruptcy, but in an ironic turn to the story, he died before a decision was reached in the case.

Dad, side angle. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

I remember a funny conversation I had with him one afternoon while we sat in the living room of my grandmother’s small ranch house in north Rome. Sunlight poured through a large bay window, past the partially opened silk curtains. Outside I could see a clear sky and trees burgeoning with leaves—a bright, saturated landscape of blue and green.

I sat in a corner of the room and he sat in a forest-green recliner covered with worn upholstery.

“What’s the name of the angel of death?” he asked me.

I was surprised by the question, and I said, “I think he’s just called the angel of death.”

“No, he has another name,” he said.

And after a few seconds it came to me. “The Grim Reaper.”

“That’s right, that’s it,” he said.

“Why do you want to know?” I asked. “Did you see him in a dream or something?

“No, but I want to know his name when he comes.”

That conversation sparked an idea for a full-length play, entitled Awaiting the Reaper. I could go on and on about my dad, but that’s the strongest memory I have of him in his waning days.

Dad in the kitchen. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

Dad never earned prestigious academic honors, never published a book, never ran a company or made enough money in his lifetime to buy a retirement home in Florida.

Instead, he toiled away in obscurity and mediocrity as a working-class person. My sister and I received no inheritance, save a small insurance policy that paid out after his death. And his shy, aloof nature created a buffer with other people, a barrier to forming deep relationships (except with a few close friends).

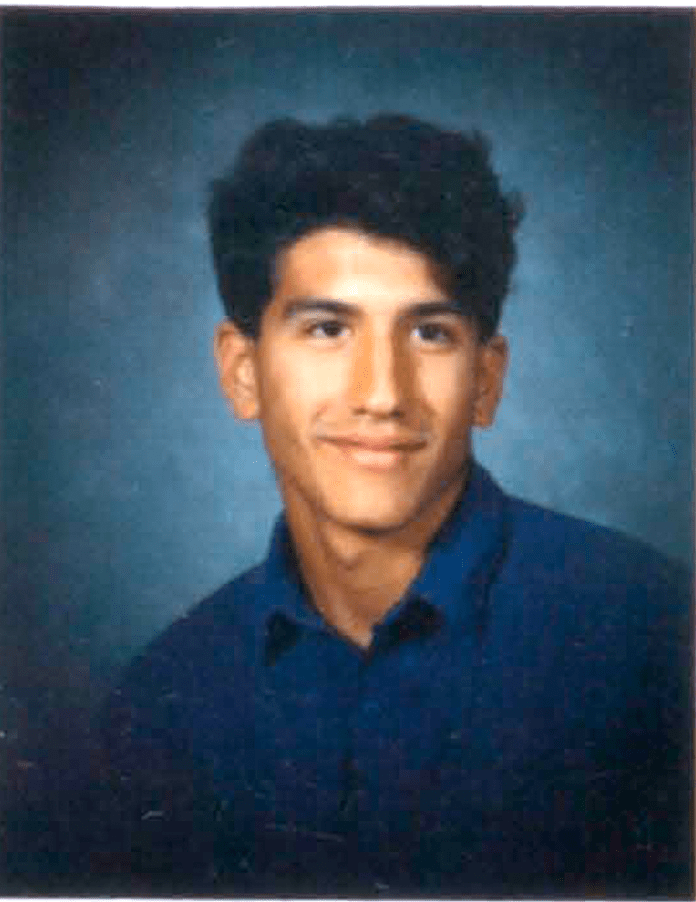

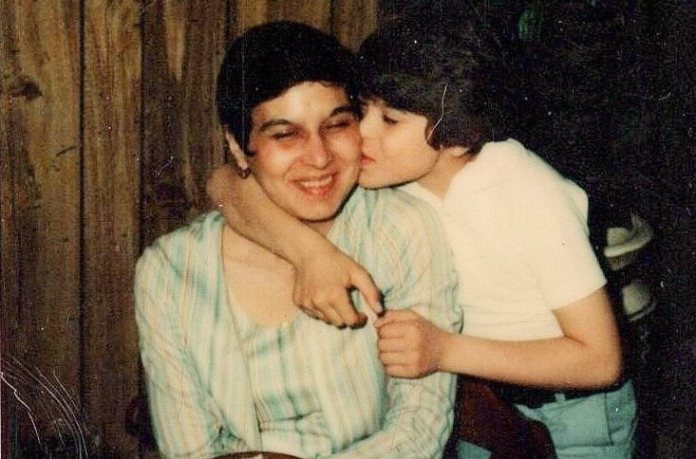

A photo of my father and me following my Confirmation in 1984.

Yet in reviewing his life, I know his kindness, work ethic, and willingness to help others set an example for me that I have tried to uphold. And the debts he accrued do not cancel out those qualities.

The one word I keep coming back to is decency. My father was a good and decent man. That may not be cause for celebration in our society. But it’s enough to fill me with pride, and I hope to carry on his values as I carry on his name.

I’ll close this post with two poems. The second one also mentions my late mother, Carmella.

The Galliano Club

From street-level sunlight to cavernous darkness,

then down a few steps and you enter The Galliano Club.

Cigar smoke wafts in the air above a cramped poker table.

Scoopy, Fat Pat and Jules are stationed there,

along with Dominic, who monitors it all,

pacing pensively with fingers clasped behind his back.

A pool of red wine spilled on the glossy cherry wood bar,

matches the hue of blood splattered on the bathroom wall.

A cracked crucifix and an Italian flag loom above,

as luck is coaxed into the club with a roll of dice

and a sign of the cross.

Pepperoni and provolone are piled high for Tony’s boys,

who man the five phone lines

and scrawl point spreads on thick yellow legal pads.

Bocce balls collide as profanity whirls about . . .

and in between tosses, players brag about

cooking calamari (pronounced “calamad”).

Each Sunday during football season,

after St. John’s noon Mass,

my father strolls across East Dominick Street

and places his bets,

catapulting his hopes on the shoulder pads of

Bears, Bills, Packers and Giants.

His teams never cover

and he’s grown accustomed to losing . . .

as everything in Rome, New York exacts a toll,

paid in working class weariness and three feet of snow.

But once inside The Galliano, he feels right at home,

recalling his heritage, playing cards with his friends.

And here he’s no longer alone,

as all have stories of chronic defeat.

Blown parlays, slashed pensions

and wives sleeping around,

constitute the cries of small-town men

who have long given up on their out-of-reach dreams.

For now, they savor the moment—

a winning over/under ticket, a sip of Sambuca

and Sunday afternoons shared in a place all their own.

Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

Vestiges

My parents are gone.

They walk the earth no more,

both succumbing to lung cancer,

both cremated and turned to ash.

With each passing year,

their images become more turbid in my mind,

as if their faces are shielded

by expanding gray-black clouds.

I try to retain what I remember—

my father’s deep-set, dark eyes and aquiline nose,

my mother’s small head bowed in thought or prayer

while smoking a cigarette in the kitchen.

I search for their eyes

in the constellations of the night sky.

I listen for their voices in the wind.

Is that Rite Aid plastic bag snapping in the breeze

the voice of my father whispering,

letting me know he’s still around . . .

somewhere . . . over there?

Does the squawking crow

perched in the leafless maple tree

carry the voice of my mother,

admonishing me for wearing a stained sweater?

Resorting to a dangerous habit,

I use people and objects as “stand-ins”

for my mother and father,

seeking in these replacements

some aspect of my parents’ identities.

A sloping, two-story duplex with cracked green paint

embodies the spirit of my father saddled with debt,

playing the lottery, hoping for one big payoff.

I want to climb up the porch steps and ring the doorbell,

if only to discover who resides there.

In a grocery store aisle on a Saturday night

I spot an older woman

standing in front of a row of Duncan Hines cake mixes.

With her short frame, dark hair, and glasses,

she casts a similar appearance to my mother.

She is scanning the labels,

perhaps looking for a new flavor,

maybe Apple Caramel, Red Velvet, or Lemon Supreme,

just something different to bake

as a surprise for her husband.

A feeling strikes me and

I wish to claim her as my “fill-in” mother.

I long to reach out to this stranger in the store,

fighting the compulsion

to place a hand on her shoulder

and tell her how much I miss her.

I fear that if my parents disappear

from my consciousness,

then I too will become invisible.

And the reality of a finite lifespan sets in,

as I calculate how many years I have left.

But I realize I am torturing myself

with this twisted personification game.

I must remember my parents are dead

and possess no spark of the living.

And I can no longer enslave them in my mind,

or try to resurrect them in other earthly forms.

I have to let them go.

I have to dismiss the need for physical ties,

while holding on to the memories they left behind.

And so on the night I see the woman

in the grocery store aisle,

I do not speak to her,

and she does not notice me lurking nearby.

But as I walk away from her,

I cannot resist the impulse to turn around

and look at her one last time—

just to make sure

my mother’s “double” is still standing there.

I want her to lift her head and smile at me,

but she never diverts her eyes

from the boxes of cake mixes lining the shelf.

Sidewalk Stories (Kelsay Books, 2017)