On this Father’s Day, I pay tribute to my two dads, the late Francis DiClemente Sr. and my stepfather, the late William Ruane. I was blessed to have these two wonderful men nurture me and influence my life. Here are some photos and writing selections honoring them.

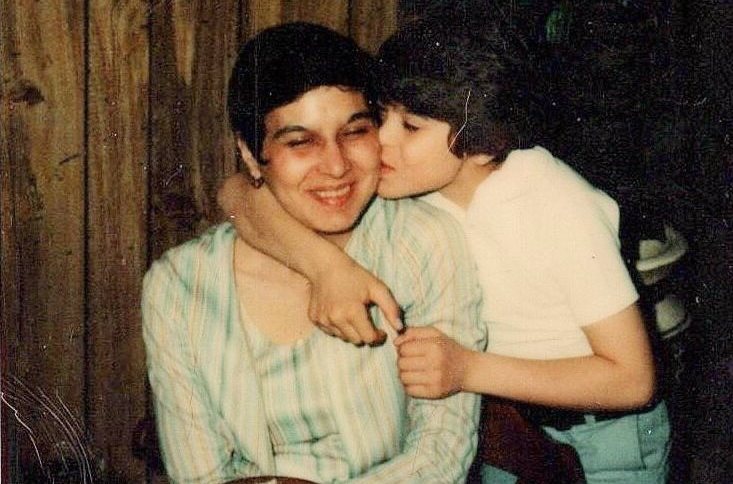

That’s me on the left with my father, mother and sister Lisa.

Open Heart

My father was born

with a hole in his heart,

and although repaired,

nothing in his life,

ever filled it up.

The defect remained,

despite the surgeon’s work—

a void, a place I could never touch.

Outskirts of Intimacy (Flutter Press, 2010) and Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

Photo of my dad and me from my Confirmation at St. John the Baptist Church in Rome, NY.

The Galliano Club

From street-level sunlight to cavernous darkness,

then down a few steps and you enter The Galliano Club.

Cigar smoke wafts in the air above a cramped poker table.

Scoopy, Fat Pat and Jules are stationed there,

along with Dominic, who monitors it all,

pacing pensively with fingers clasped behind his back.

A pool of red wine spilled on the glossy cherry wood bar,

matches the hue of blood splattered on the bathroom wall.

A cracked crucifix and an Italian flag loom above,

as luck is coaxed into the club with a roll of dice

and a sign of the cross.

Pepperoni and provolone are piled high for Tony’s boys,

who man the five phone lines

and scrawl point spreads on thick yellow legal pads.

Bocce balls collide as profanity whirls about . . .

and in between tosses, players brag about

cooking calamari (pronounced “calamad”).

Each Sunday during football season,

after St. John’s noon Mass,

my father strolls across East Dominick Street

and places his bets,

catapulting his hopes on the shoulder pads of

Bears, Bills, Packers and Giants.

His teams never cover

and he’s grown accustomed to losing . . .

as everything in Rome, New York exacts a toll,

paid in working class weariness and three feet of snow.

But once inside The Galliano, he feels right at home,

recalling his heritage, playing cards with his friends.

And here he’s no longer alone,

as all have stories of chronic defeat.

Blown parlays, slashed pensions

and wives sleeping around,

constitute the cries of small-town men

who have long given up on their out-of-reach dreams.

For now, they savor the moment—

a winning over/under ticket, a sip of Sambuca

and Sunday afternoons shared in a place all their own.

Outskirts of Intimacy (Flutter Press, 2010) and Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

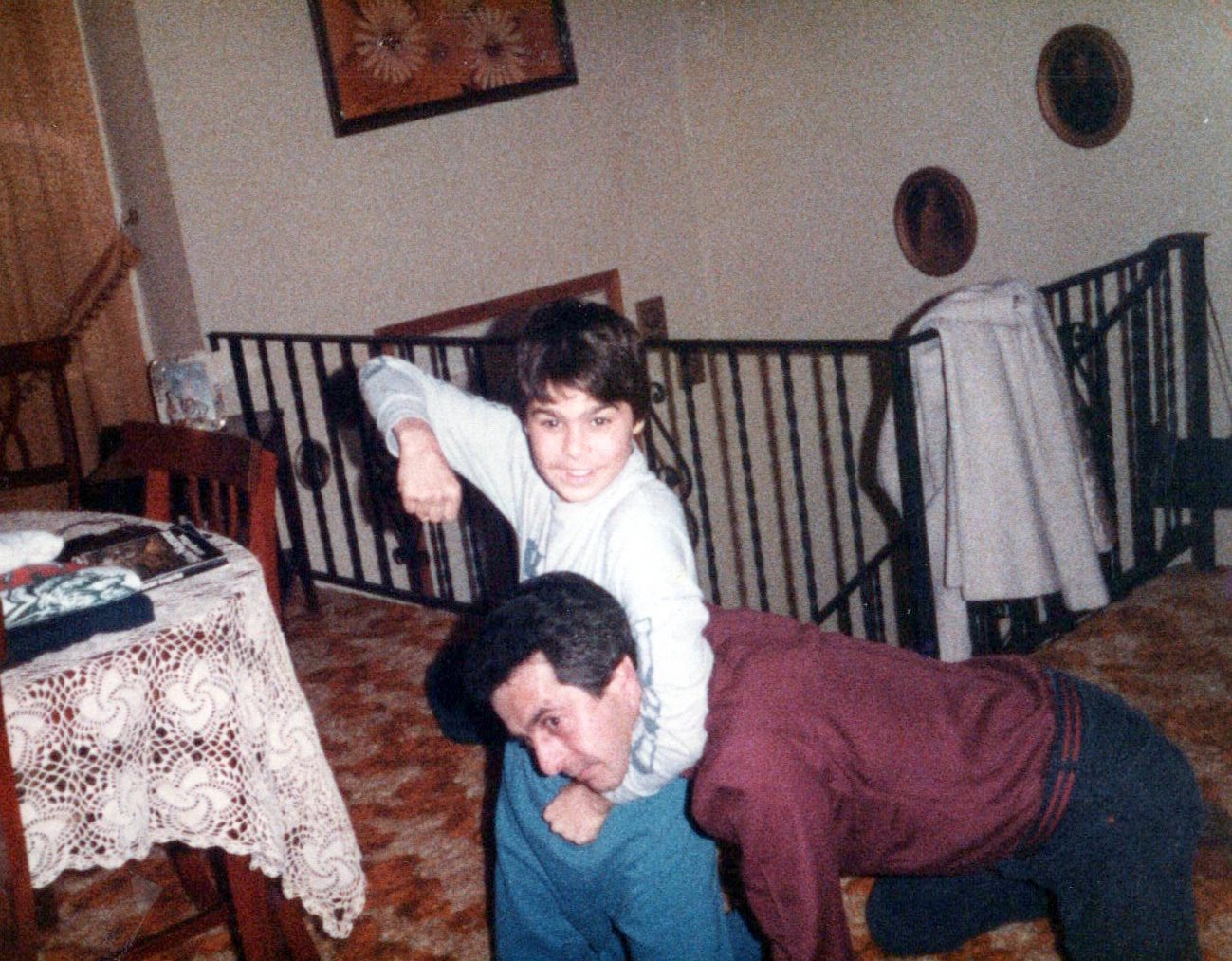

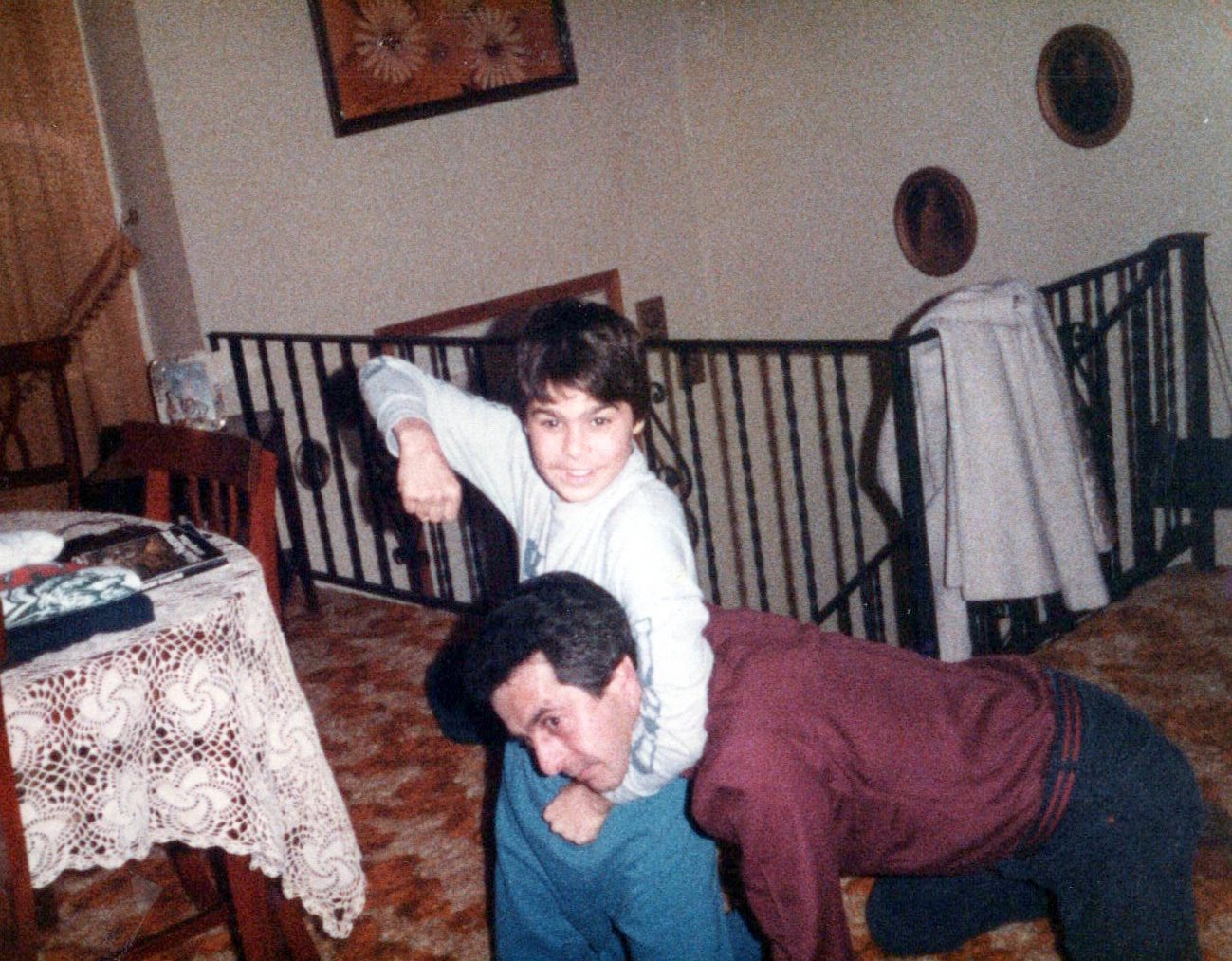

Dad and I rolling around on the floor.

Diagnosis

Dad put the car in park and let it idle,

and as I slid into the passenger seat and adjusted myself,

he leaned over and kissed me on the cheek,

his tan winter coat brushing against the steering wheel.

I felt a trace of his razor stubble against my skin,

and I could smell a faint odor of Aqua Velva or Brut,

combined with cigarette smoke.

The heater hummed, and he lowered the blast of air.

I wondered why we weren’t moving yet.

He wasn’t crying,

but he appeared on the verge of spilling emotions.

“What’s the matter, Dad?” I asked.

“The hospital called your mother today.”

He switched on the overhead light,

reached into his jacket pocket,

and pulled out a torn piece of paper.

“Here,” he said, handing me the slip of paper,

“This is what they think you have.

I wrote it down, but I don’t think I spelled it right.”

Scribbled in faint blue ink was a misspelling

of the word “craniopharyngioma.”

My father’s voice cracked as he said,

“It’s cranio-phah-reng,

something like that . . . oh, I don’t know,

it’s some kind of brain tumor.”

I looked at the paper and felt a wave of satisfaction

as my father let out a sigh.

He seemed locked into position in the driver’s seat,

unable to shake off the news and go through the motions

of putting the car in gear and driving away.

We clutched hands, and I said, “It’s OK, Dad. Don’t worry.

But what do we do now? What’s next?”

“You have to go back there for more tests,” he said.

You may need surgery.”

“All right,” I said.

He switched off the overhead light,

and we exited the parking lot.

We grew silent inside the car

as we passed the naked trees lining Pine Street

in our city of Rome, New York.

While my father was crestfallen,

I felt elated as I sat in the passenger seat.

The CT scan with contrast had given me

a medical diagnosis—

a reason for my growth failure at age fifteen.

It explained why my body had not changed,

why I had not progressed through puberty,

and why I was so different from the other boys my age.

I still considered myself a physical anomaly,

but the tumor proved it wasn’t my fault.

That knowledge gave me satisfaction

and a stirring of excitement.

I looked down at the piece of paper again

and studied the word—“craniopharyngioma.”

I tried to sound it out in my head while my dad drove on.

I thought the word would roll off my tongue

like poetry if I said it out loud.

Craniopharyngioma. Cranio-Phar-Ryng-Ee-Oh-Mah . . .

sort of like onomatopoeia.

The Truth I Must Invent (Poets Choice, 2023)

Dad in the kitchen. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

Death Mask

Assume the death mask,

put on your final face

like those insolent characters

in that Twilight Zone episode—you know the one,

with their cruel faces contorted

and fixed there for all time’s sake.

My father wore his death mask.

He kept it on even though I arrived after his passing

on that soft warm August evening.

I’ll never forget the way he looked,

with his mouth agape, eyes vacant, cheeks sunken,

body withered and shriveled,

curled up in the fetal position on his deathbed

in my grandmother’s sweltering death house.

I allowed myself to look at him for just a moment.

I then turned around and left him alone

in his small bedroom.

I did this for my benefit, since I wanted to remember him

as a father and a man

and not as a corpse in a locked-up state.

This is because the death mask grips its lonely victim

and sucks out the life and extinguishes the person.

I shuffled into the living room,

rejoining the Hospice nurse and the neighbors

who came across the street

to comfort my grandmother and express remorse.

And Grandma, still acting as host

despite the occasion and the heat,

asked me to make a pot of coffee for her guests.

The neighbors sat on the old, out-of-style couches

and chairs in my grandmother’s ranch home

off Turin Road in north Rome.

They conversed in hushed tones and sipped coffee

while we waited for the workers from the funeral parlor

To drive up to the house and wheel away my father.

Outskirts of Intimacy (Flutter Press, 2010) and Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

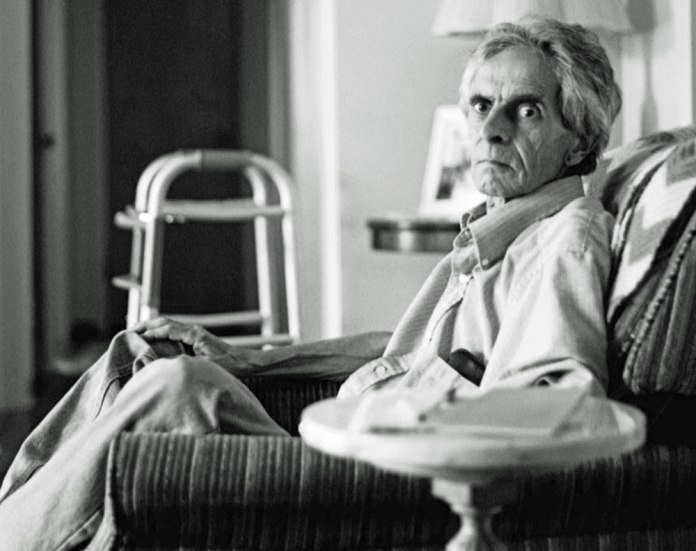

Dad in his chair. It’s out of focus, but I love how he looks directly at the camera. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

St. Peter’s Cemetery

I extend a hand to touch an angel trapped in marble.

Its face is cool and damp, like the earth beneath the slab.

I pose a question to my deceased father,

Knowing the answer will elude me.

For his remains are not buried in this cemetery,

But instead rest on a shelf in my sister’s suburban Ohio house.

Outskirts of Intimacy (Flutter Press, 2010) and Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

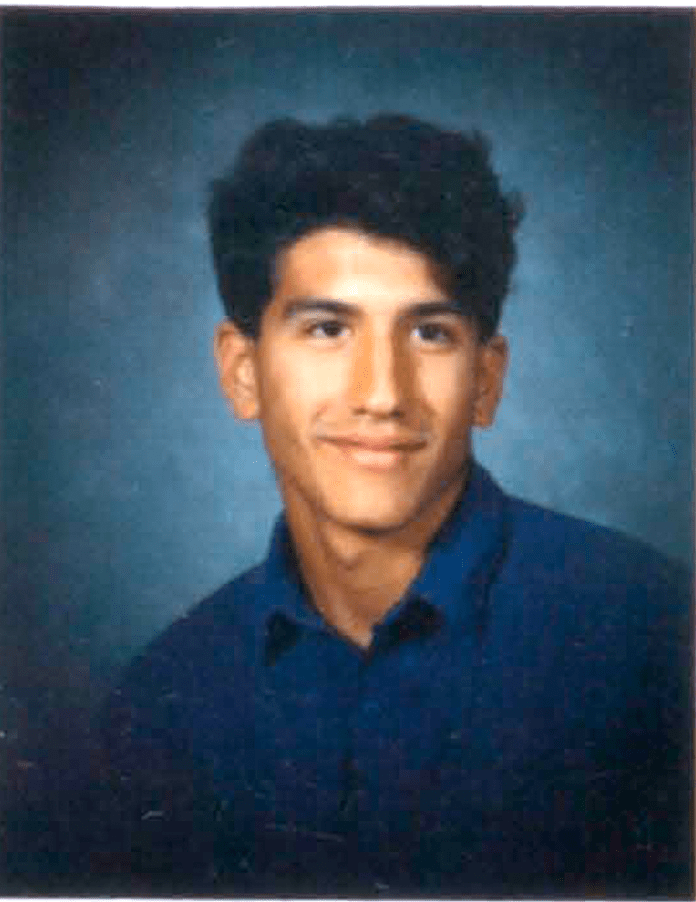

Dad rocking the denim cut-off shorts.

Vestiges

My parents are gone.

They walk the earth no more,

both succumbing to lung cancer,

both cremated and turned to ash.

With each passing year,

their images become more turbid in my mind,

as if their faces are shielded

by expanding gray-black clouds.

I try to retain what I remember—

my father’s deep-set, dark eyes and aquiline nose,

my mother’s small head bowed in thought or prayer

while smoking a cigarette in the kitchen.

I search for their eyes

in the constellations of the night sky.

I listen for their voices in the wind.

Is that Rite Aid plastic bag snapping in the breeze

the voice of my father whispering,

letting me know he’s still around . . .

somewhere . . . over there?

Does the squawking crow

perched in the leafless maple tree

carry the voice of my mother,

admonishing me for wearing a stained sweater?

Resorting to a dangerous habit,

I use people and objects as “stand-ins”

for my mother and father,

seeking in these replacements

some aspect of my parents’ identities.

A sloping, two-story duplex with cracked green paint

embodies the spirit of my father saddled with debt,

playing the lottery, hoping for one big payoff.

I want to climb up the porch steps and ring the doorbell,

if only to discover who resides there.

In a grocery store aisle on a Saturday night

I spot an older woman

standing in front of a row of Duncan Hines cake mixes.

With her short frame, dark hair, and glasses,

she casts a similar appearance to my mother.

She is scanning the labels,

perhaps looking for a new flavor,

maybe Apple Caramel, Red Velvet, or Lemon Supreme,

just something different to bake

as a surprise for her husband.

A feeling strikes me and

I wish to claim her as my “fill-in” mother.

I long to reach out to this stranger in the store,

fighting the compulsion

to place a hand on her shoulder

and tell her how much I miss her.

I fear that if my parents disappear

from my consciousness,

then I too will become invisible.

And the reality of a finite lifespan sets in,

as I calculate how many years I have left.

But I realize I am torturing myself

with this twisted personification game.

I must remember my parents are dead

and possess no spark of the living.

And I can no longer enslave them in my mind,

or try to resurrect them in other earthly forms.

I have to let them go.

I have to dismiss the need for physical ties,

while holding on to the memories they left behind.

And so on the night I see the woman

in the grocery store aisle,

I do not speak to her,

and she does not notice me lurking nearby.

But as I walk away from her,

I cannot resist the impulse to turn around

and look at her one last time—

just to make sure

my mother’s “double” is still standing there.

I want her to lift her head and smile at me,

but she never diverts her eyes

from the boxes of cake mixes lining the shelf.

Sidewalk Stories (Kelsay Books, 2017)

##

A fictional poem with a Father’s Day theme.

Father’s Day Forgotten

Daddy and Christi parted ways at a bus depot

In the early morning hours.

No big scene, just a kiss on the cheek,

Then she turned around and was gone for good—

Hopping aboard a Trailways bus

Headed westbound for Chicago.

And she never looked back.

Daddy went home to his beer bottle and sofa seat,

And he drew the living room curtains

On the rest of the world,

Letting those four eggshell walls close in

And swallow him up,

Wasting away in three empty rooms and a bath.

And the memories can’t replace his lost daughter and wife.

So he tries not to remember his mistakes

Or how he drove them away.

Instead, he recalls Halloween pumpkins

Glowing on the front porch,

Training wheels moving along the uneven sidewalk,

Little hands reaching for bigger ones in the park,

And serving Saltine crackers and milk

To chase away the goblins that haunted

Dreams in the middle of the night.

Now Christi has a life of her own,

And she lets the answering machine catch

Daddy’s Sunday afternoon phone call.

She never picks up and rarely calls back.

So Daddy returns to the green couch

Pockmarked with cigarette burns.

He closes his eyes, opens the door to his memory vault

And watches the pictures play in slow-motion.

He rewinds again and again,

Without noticing the film has faded

And the little girl has stepped out of the frame.

Vestiges (Alabaster Leaves Publishing/Kelsay Books, 2012) and Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

##

Carm and Bill celebrating Bill’s birthday.

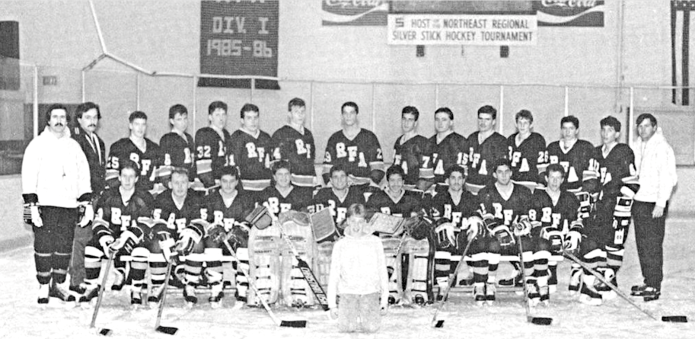

I never called Bill “Dad,” but I considered him a second father instead of a stepfather. He and my mother, Carmella, started dating around 1985 and were married in 1990. From about the time I turned fifteen, during my formative years, Bill was always there, and he played an instrumental role in my transition from boy to man.

Weekend in Albany

Night—diminished faith now fights for restoration,

aided by rosary beads pressed between the gnarled fingers

of the retired Sisters of the Academy of Holy Names.

And silent petitions are mouthed

in an air-conditioned hospital chapel,

as Sister Carmella—my Aunt Theresa—

storms the gates of heaven for healing intervention,

sending out special pleas to Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

Inside the surgical Intensive Care Unit,

fluorescent lights reveal my stepfather Bill’s post-op image.

The sight of his figure catches me unprepared—

glassy eyes, belly stained with iodine,

an incision running down the sternum,

and a ventilator forcing air into his smoker’s lungs.

Mom stays close to his bed,

afraid to look away or leave the room.

Her small body trembles and

displays the effects of chemotherapy’s wrath,

evident in hollow cheeks

and in the absence of her black hair.

Unbearable heat conquers the Capital District,

and Mom finally crumbles when our used Chevy Blazer

hisses and groans and stalls along New Scotland Avenue.

She sits down on the roadside curb, dejected.

Her tears cannot be held in any longer . . . they gush forth

as she holds a cigarette and sips a lukewarm cup of coffee.

Almost in slow motion,

a few drops fall toward her Styrofoam cup.

I reach out to catch them,

but they slip through my outstretched fingers.

And after two days in Albany, my sister and I

must leave our mother to return home to Toledo.

On the flight back, in a plane high above

the patchwork of northwest Ohio’s farms and fields,

streaks of pink and lavender compose the sunset’s palette.

And I realize all I can do is pray;

I’m left to trust faith in this family crisis.

I ask God to hasten Bill’s recovery,

while giving Mom the strength to abide.

I lean against the window

as the plane touches down in Toledo.

I close my eyes and consider if my prayers

are just wishes directed toward the clouds.

No matter, I tell myself, pray despite a lack of trust.

And so I do. I focus my thoughts on my stepfather

breathing without a ventilator

and being moved out of the ICU.

Outskirts of Intimacy (Flutter Press, 2010) and Dreaming of Lemon Trees: Selected Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2019)

##

This essay was published in 2013 in Star 82 Review.

Man in the Chair

It is late in the afternoon on a fall or winter day, and I am visiting my mother and stepfather at their home in Rome, New York. They are sitting in their family room watching TV; if I had to guess, I’d say the show is Judge Judy, Criminal Minds or NCIS.

My stepfather Bill, who owns his own contracting business, is reclining in his favorite chair, wearing a work-stained hoodie and sipping a cup of coffee. I walk into the room and sidle up to him. I put my hand on the bald crown of his head, which has a fringe of brownish-gray hair on the sides, and I feel the warmth emanating from his skull. Often when I do this, Bill will say, “God, your hand is freezing.” But he does not say anything, and I leave my hand on top of his head and take a glance at the television screen while darkness gathers outside the windows.

A sick realization makes me shudder. I pull my hand away because I recognize in the moment that the head of this man I love could, in a matter of seconds, be crushed with a baseball bat or cracked open with an ax blade. Blood could splatter against the walls, and he would slump over in the chair, inert.

And I think this not because I am homicidal or possess a desire to kill my stepfather. Quite the opposite. Fear sets in because I realize the man sitting in the chair, with a beating heart, functioning brain and sense of humor, could be gone in an instant. He could be animated in one moment and his breath snuffed out in the next.

Bill getting a haircut from George, a barber in Rome, New York. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

Most likely my stepfather will not be killed by a blow to the head or a tree crashing through the house. A heart attack, stroke or cancer will probably get him in the end. And while I already know this, I pause and allow this knowledge to sink in, so I will appreciate him better.

A year or two after this dark afternoon, my mother would lose her battle with cancer. And her death would remind me that we do not live life all at once. It’s not one big project we need to complete by a deadline or a trip to Europe you have planned for years.

Instead, we experience life in small doses, tiny beads of time on a string. And it helps to recognize them, to acknowledge you are present and alive even in the most mundane circumstances—while you are talking with co-workers in the parking lot before heading home for the day, running errands, doing laundry, baking a chocolate cake, tossing a football with friends and reading to your kids at bedtime. These are subplots that drive our stories forward. They are not exciting. They are not memorable. But they are part of our existence, and we must value them before they and we are gone.

So, after I pull my hand away from Bill’s head, I decide to sit on the couch next to my mother. She hates when people talk during a program because it distracts her, so I look at the screen even though I am not interested in the show, and I do not say a word. But during a commercial break, she mutes the sound with the remote control, and Bill and I converse about something. And I can’t remember the topic we discussed, and it doesn’t really matter.

##

These clown wind chimes once hung on the walkway leading to Bill’s back door.

Black and white clown wind chimes. Photo by Francis DiClemente.

I wrote this poem in haste after finding out that Bill passed away on Dec. 25, 2021.

Poem for Bill

I wonder where he is right now.

Is he soaring through the layers

of space between earth and heaven?

Is he sitting in a holding cell,

awaiting his purgatory sentence?

Is his body weightless

and his brain wiped clean?

Does he know he’s dead?

Or is there nothing left to know?