I am celebrating an important milestone today—the 40th anniversary of my first brain surgery to remove a benign tumor engulfing my pituitary gland. I have written about this ordeal many times in the past, including in this long 2014 post.

On this day, four decades ago, surgeons cracked open my skull and extracted the craniopharyngioma that had stunted my growth and delayed my transition from boy to man.

In this essay, I reflect on my experience as a teenager in 1984 while a patient at SUNY Upstate Medical Center (renamed Upstate University Hospital) in Syracuse, New York. I am limiting the narrative period to the day of surgery and my immediate recovery.

Upstate University Hospital

Surgery Day: An Essay

1.

Early morning. Blackness. I can smell the breakfast trays delivered on the hospital floor—watery eggs, ham and bacon, soggy oatmeal, and weak tea and coffee. The noise outside my room grows as patients awaken and nurses draw blood and administer medicine.

My appointment with the medical intervention team has arrived. I am fifteen years old and ready for surgery day, prepared for the trauma that awaits me on the table. My head will be shaved, and my skull sawed open. The tumor growing in my head—wrapped around my pituitary gland and stifling my maturation—will be plucked free, yanked out like an infected molar and then examined under a microscope to determine its classification. We must name our enemies to defeat them.

Once removed, the lesion will relinquish dominion over my body. I will be cut loose from its tentacles. The surgery will disrupt my endocrine system, leading to a permanent condition known as hypopituitarism and propelling me on a long road toward “catch-up” growth and development.

A photo of my father and me two months before the operation in 1984.

2.

A nurse enters my room and hands me a small plastic cup filled with a few pills. “This will just relax you,” she says as I swallow the pre-surgery drugs. About a half-hour later, she returns and says, “It’s time for you to go down now.” A softness squishes against the edges of my mind; I am drifting from consciousness.

An orderly comes to take me away—filling nearly the entire space inside the door frame. A hulking figure with thick, black hair, a black beard, and muscular forearms, he reminds me of Bluto from the Popeye the Sailor cartoons. But for some reason, I call him Hugo.

“OK, Hugo,” I say, “I’m ready now.” Hugo helps me slide over from my bed to a stretcher as the nurse covers me with a sheet and a blanket.

My family gathers around me, bending down to kiss me and wish me “good luck.” What does “good luck” mean on the operating table? I wonder.

Tears stream down my mother’s cheeks, which are red and wind-burned and feel cold against my skin as she kisses my face and forehead; she squeezes my hand and then releases her grip and steps away.

Hugo unlocks the wheels of the gurney and steers it out of the room and into the hallway. Even though I am sleepy, I stay awake for the ride, keeping my eyes open and watching the panels of fluorescent lights pass overhead as we make our way through the hospital corridors and into an elevator. We take a silent ride down to the surgical wing.

The temperature drops when we enter the frigid, sterile operating room. A chill runs over my body; my lips tremble as gooseflesh buds on my arms.

The surgical team members buzz around the operating room, each doctor or nurse carrying out a specific task. They transfer me from the stretcher to the operating table. An overhead light shines into my eyes while I lay splayed on the table.

A nurse covers me with an extra blanket and stretches tight, white stockings over my calves. She says the stockings will help to prevent blood clots after surgery.

One of the doctors sits down near the table and says he will shave my head. When he asks me if I want my whole head sheared or just the front, I make the mistake of telling him to clip only the front. As a result, weeks after the surgery, my hair remains uneven—bald in front and growing long in the back—similar to the long hair sticking out the back of helmets worn by hockey players with mullets.

After they jab an IV in my arm, I grow drowsy, my eyelids shutting; but before I drift off, I tell one of the nurses that I need to pee. The woman chuckles and says, “Oh, you don’t have to worry about that now. We’ve already put in a catheter.”

And then I leave the world—falling under the power of general anesthesia for about eight-and-a-half hours while the surgeons perform their work.

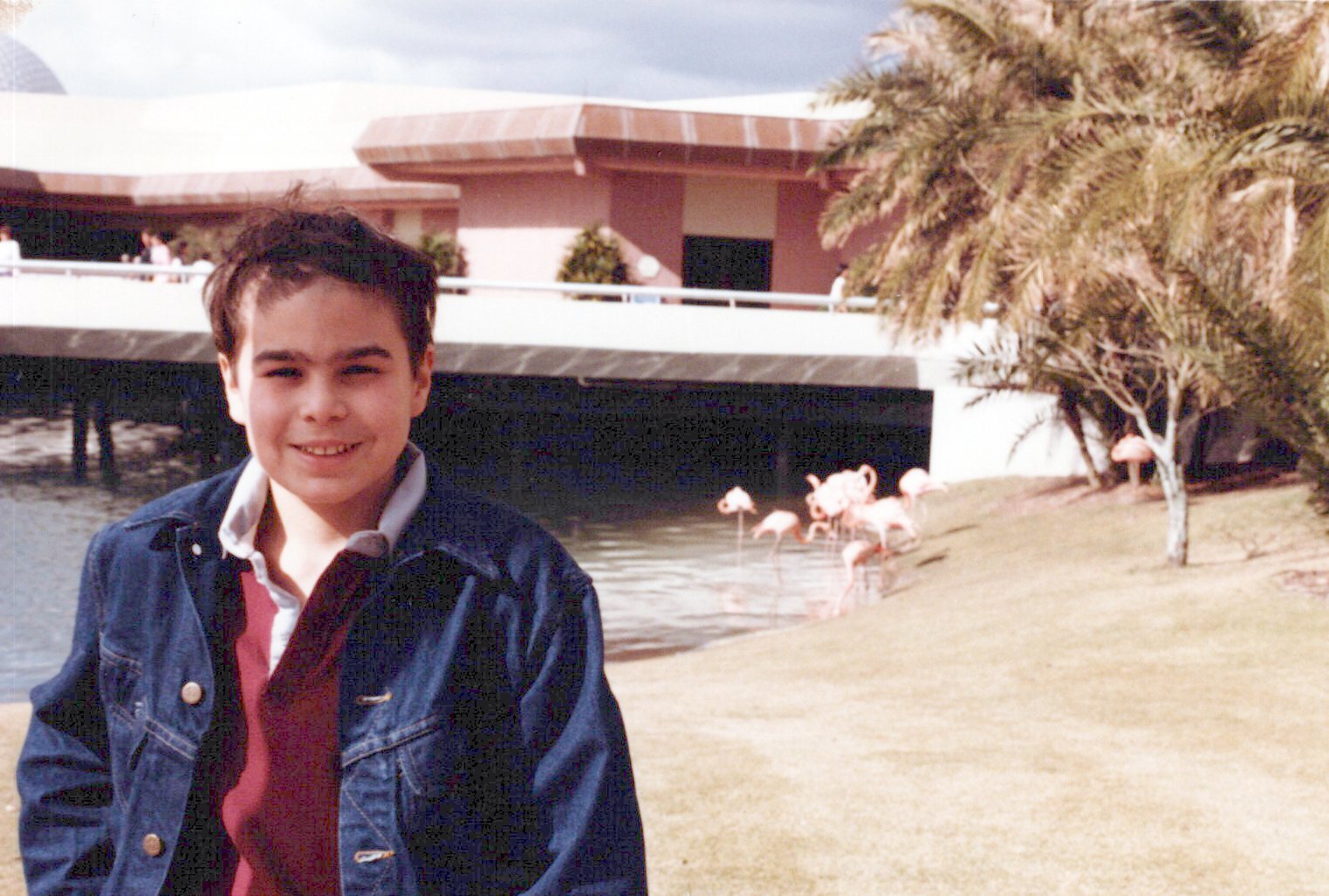

At Walt Disney World in February 1985.

3.

I have often wondered where I traveled to during that gap of time. What realms or landscapes did I explore in my mind while my skull lay open and I remained unconscious on the operating table?

Here is me stepping out of the story momentarily to travel back in time and investigate the scene. It’s a fantasy of the man I hoped I would become once the surgeons extracted the tumor. It’s the future I had envisioned for myself—marked by maturation and normalcy, playing the role of a fully formed male accompanied by a female partner.

A green canopy of trees. A trilling stream. Sunlight filtering through leaves overhanging a hiking path. Birds chirp, and tree limbs sway in the wind.

Boots touch the soft, muddy earth. A man emerges from a wooded path. He is dressed in a red checkered flannel shirt, tan khakis, and hiking boots, and he carries a knapsack on his shoulders. He is about five feet six inches tall, lean and muscular, and has a slight beard.

A twig snaps, and we see a woman walking out of a clearing. She’s wearing a fleece sweatshirt, jeans, hiking boots, and a backpack. The two figures stride toward one another, share a kiss, and then grasp hands. Sunlight bathes them as they leave the clearing and start walking on a path leading over a ridge. They climb the slight incline and disappear as they walk down the other side, their bodies concealed by the curve of the Earth.

Late high school or early college years.

4.

I wake up in a bed tucked in a corner of the surgical intensive care unit. I feel dizzy, and a dull, continuous ache presses against my head as if my skull is being squeezed in a vice. Nurses inject the opioid Demerol into my thighs over several hours to alleviate the pain, and I keep drifting in and out of sleep. I hear machines beeping and the sound of a respirator somewhere on the floor. The gentle sound of the ventilator puts me at ease as I listen to it—in and out, in and out, in and out.

EKG stickers are pressed to my chest, and machines monitor my heart rate and blood pressure. Vaseline has been smeared on my eyelids and eyelashes, clouding my vision, and I feel like I am straining to see from under the cover of a heavy, wet blanket. The white stockings the surgical team had given me are pulled up to my knees and constrict the circulation in my lower limbs.

I feel small—shriveled up in the bed like a green-gray alien being prodded by U.S. government doctors and scientists on an operating table in Roswell or Los Alamos, New Mexico. A scar runs the entire length of my head, from the tip of my right ear to the tip of my left ear. I tap a slight dent in my skull (produced by a right frontal craniotomy during surgery), about the width of two fingers, just above my forehead on the right side.

The stitches itch, and I reach up to feel the thick, black threads. I wonder if I resemble a twisted version of the Mr. Met mascot.

5.

But I feel relieved because I have awakened from the operation, and my brain function remains intact. Some doctors lean over my bed and ask me a series of questions: Do I know my name, the current year, the president of the U.S., and the name of the city I am in? I answer the questions correctly, and when instructed, I squeeze their fingers, wiggle my toes, puff my cheeks, stick out my tongue, and follow a penlight with my eyes.

My senses function properly, as I can see, hear, speak, and smell. I can form thoughts, and the trauma of the surgery has not altered my mental ability or effaced my memory.

My mother, father, sister, and Aunt Teresa huddle around my bed, their faces beaming like those of Dorothy’s relatives in the scene when she wakes up from the dream at the end of The Wizard of Oz.

“Hey, buddy,” my dad says.

My mom leans over the bed rail, kisses my face and eyelids, and says, “You did great, honey, just great.”

“Yeah, Dr. B. said he got most of it,” Dad says.

“Was it big?” I ask.

My mom holds up her right thumb, indicating the size of the tumor. “It was about the size of a thumb,” she says. She caresses my face and adds, “Dr. B. said there’s a little bit left over, but we don’t need to worry about that now.”

“OK,” I say, closing my eyes and returning to sleep.

High school graduation in 1987.

6.

I wake up on the first night with a raging thirst in my parched throat. I feel like I have been deprived of water for days. But because the doctors are concerned about swelling in the brain, they load me with corticosteroids and restrict my fluid intake. My face is swollen, and I feel bloated from the steroids; I am not allowed to drink water, but I am permitted to suck on ice chips.

However, late in the evening, with the lights dimmed on the floor after visiting hours have ended, I turn my head, look around, and notice a sink in the corner, only a few feet away from my bed.

Somehow, despite being woozy, I lower the bed rail, swing my legs out to the side, and climb out of bed. I try to be quiet as I wheel my IV stand toward the small, stainless-steel sink. I turn on the foot pedal faucet, cup my hands, and gulp the water like it’s rushing in an icy mountain river.

The cold liquid pours down my throat and gives me immediate relief. I want to stay here and drink more water, but a man—a male nurse or an orderly—races toward me and pulls me away from the sink.

“What are you doing?” he yells. “You just had brain surgery.”

He then escorts me back to bed, swings my legs over, covers me with the blankets, and lifts the bed rail.

“Now, don’t get up again,” he says. “What do you wanna do, crack your head open and screw up the work those surgeons did?”

And now tucked back into bed, I resume sleeping, drifting off until the next wave of pain hits, and I press the call button to request another dose of Demerol.

##

Recalling these past forty years, I run a tally of my surgeries at Upstate. The number stands at six—counting the initial surgery in 1984 and the subsequent operations to remove tumor regrowth in 1988, 2011, 2012 (Gamma Knife), 2020 (Gamma Knife), and 2023.

I have some double vision when looking at things up close and to my extreme right (right sixth nerve palsy), and I must be hyper-vigilant in the management of my care to treat my hypopituitarism. But except for my corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis (unrelated to the tumor), I am a healthy, middle-aged man.

My next MRI is scheduled for Dec. 18. And with the stubborn resilience of craniopharyngiomas, I know more surgeries (or radiation treatments) loom in the future. But I face each day with gratitude, recognizing how lucky I am to have survived the scalpel on multiple occasions. I also don’t look beyond each six-month window of time between MRIs. Once my current neurosurgeon orders the next MRI, I go about my life without thinking about the tumor still lurking in my head.

Late high school or early college years.

##

And because of the significance of the number 40 on this anniversary date, I’ll leave you with U2 playing “40” live at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Colorado in 1983.