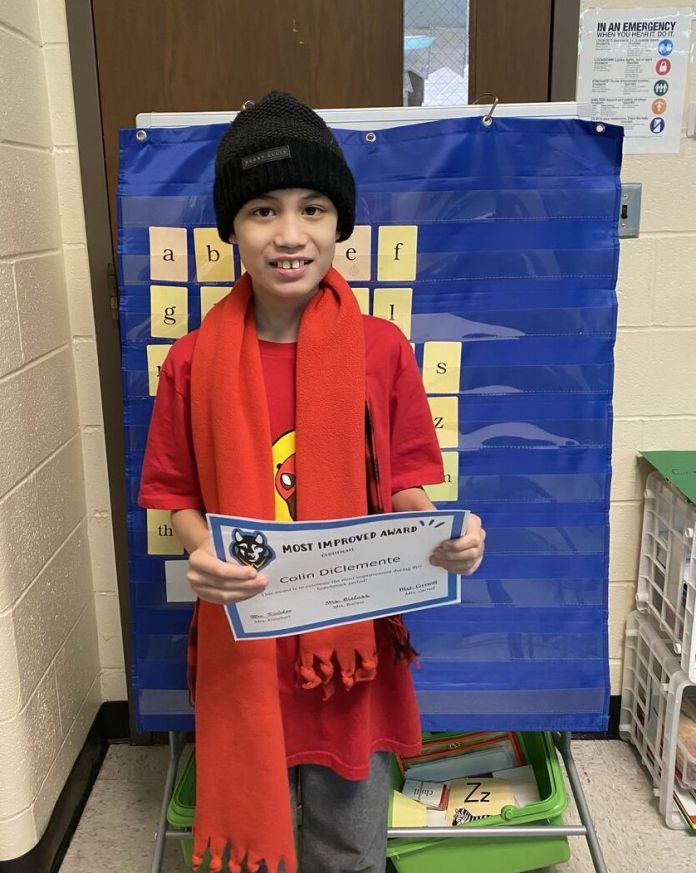

My son, Colin, turns ten years old today. I wasn’t planning to write about his birthday, but the significance of the occasion struck me as I warmed my coffee in the microwave this morning.

And right or wrong, every thought and emotion about Colin is filtered through the lens of his autism. He was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder in 2018. I wrote about that experience in this essay.

I realize how lucky I am to be Colin’s dad, especially since I was so late to the game of marriage and family. His presence reframes my existence. My job, my creative ambitions, and everything else in my life are secondary to being a good husband to my wife, Pam, and a good father to Colin.

Before rushing off to work, I wanted to share some previously published poems about parenthood and Colin, along with some photos of him.

Colin Joseph DiClemente at the pediatrician’s office.

Entrance

As blood, urine and feces stain the hospital sheets,

a nurse tells a mother-to-be,

“Honey, don’t be embarrassed.

What happens in the delivery room,

stays in the delivery room.”

The mother-to-be moans and sheds tears

as the epidural wears off and the labor reaches its climax

with a medieval torture method known as “Tug of War”—

sheets wrapped around ankles, legs hoisted in the air

and pulled apart as the mother-to-be screams

and squeezes her muscles and makes the final push until …

a tiny male human, slimy and alien-looking,

pops out of the womb with a full head of downy, brown hair

and soft, pliable ears like a Teddy bear.

The mother blurts out three words:

“Baby, baby, baby.”

The doctor transfers the squirming newborn to her breast,

and the two bond with skin-to-skin contact.

Love and happiness flow.

The task is completed, the effort done.

The child has safely entered the world.

But the real hard work has just begun.

Colin Joseph DiClemente. Age 2 years, 8 months.

The Great Equalizer

The democratic nature of parenthood.

It doesn’t matter who you are—

man, woman or trans, gay or straight,

Black, white or any other shade,

tall or short, skinny or fat, rich or poor—

when your toddler is wailing

in a grocery store or shopping mall,

when the feet are stomping, the arms swinging,

the cheeks reddened and the tears rolling—

all you want to do is pick up the child

and make the crying stop.

Wealth, social standing and comely looks

mean nothing to kids; they’re not impressed

by your credentials and you can’t negotiate

with these little angels and tyrants who rule the world.

Two clichés apply here:

parenting wipes the slate clean

and levels the playing field.

All mothers and fathers desire the same thing—

the health, safety and

development of their offspring.

The goals are simple amid the frenzy

of a life marked by stress and lack of sleep.

They are: eat the chicken nuggets, drink the apple juice,

recite the alphabet, put away the toys, finish the milk,

wave bye-bye and go down easy at nap time.

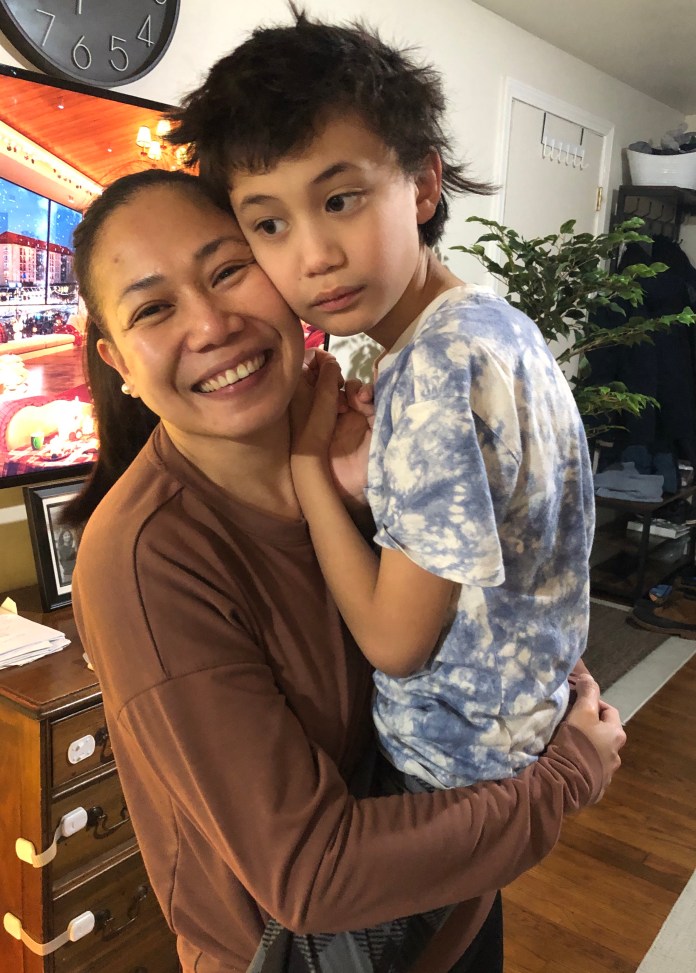

Pam and Colin outside NBT Bank Stadium.

Human Anatomy

Beneath the ribs

beats the heart

of a child,

waiting for its mother,

longing to be fed—

not just with milk and food,

but also with love.

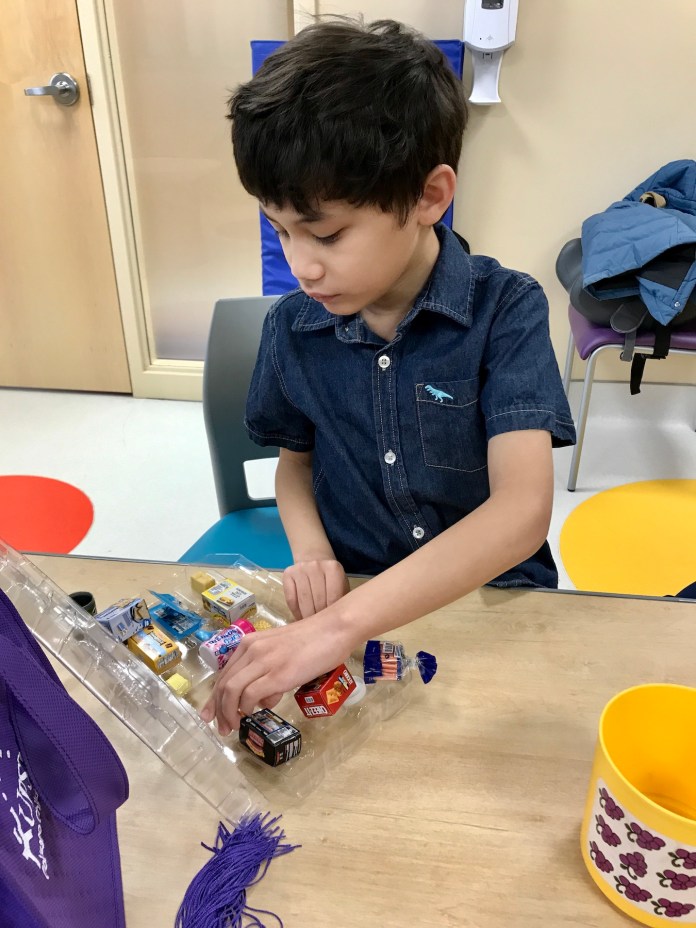

Colin playing in the feeding therapy room.

Nap Time

Late afternoon, Sunday, gray light

seeping in through parted curtains.

Mother and baby sleeping on the couch,

hair tousled, right cheek against left breast,

elbows curved at equal angles.

I am awake, drinking coffee,

watching their chests rise and fall,

and trying not to make any noise.

My whole life revealed in the space

of three sofa cushions occupied by

two human beings who need me.

Soon the boy will stir;

soon he will squirm and cry, scatter his toys

and race around the cluttered living room.

Soon we will fix dinner

and wash dishes and take out the garbage.

But now time is suspended like a Rod Serling

freeze frame in a Twilight Zone episode—

a halting of activity, a pause in my Sunday

leading to reflection and gratitude for my blessings.

Warmth, safety and responsibility

are the words that pop into my head

while I observe mother and child stretched out together.

I don’t think about what I lack

or what I hope to attain and achieve.

In this moment, I have everything I need.

Pam and Colin.

Exam Room Revelation

“Autism Spectrum Disorder.”

The moment those words

escape the doctor’s lips,

our son’s future

appears bleaker.

The phrases

“special needs,

delayed communication

and lack of

social interaction” follow.

Sorrow for my son Colin

gushes inside me.

I feel sadness

for the challenges

he will endure,

and for his inability

to have a normal life.

In this case,

love proves impotent.

You can’t intercede

with your heart.

And compassion won’t fix

the little boy

sleeping in his bed

as I type out

this bad poem

while lamenting

the diagnosis.

But love for him

does not decrease.

Instead, it grows stronger.

I am grateful

for the blessing

of the boy he is …

and the man

I hope

he will become—

regardless of autism.

Bedtime

Eventually, I’ll fall asleep,

but until then my kid

keeps annoying me,

flicking on the bedroom light

and screaming incoherent phrases—

bits of songs that make

some sense inside his mind.

Telling him “shh” does no good,

and I can’t decipher the words he speaks,

but I do enjoy hearing the sounds they make

when they escape his mouth,

as I close my eyes and try to get some sleep.

Crying at Bedtime

Nothing prepares a parent

for the tantrums of an autistic child.

There’s no well of patience to draw from.

You adapt. You divert. You distract.

You do whatever it takes to calm the child down—

until you earn that blessed moment of peace,

when his eyelids drop and he drifts off to sleep,

his small body folded in the cradle of your arms.

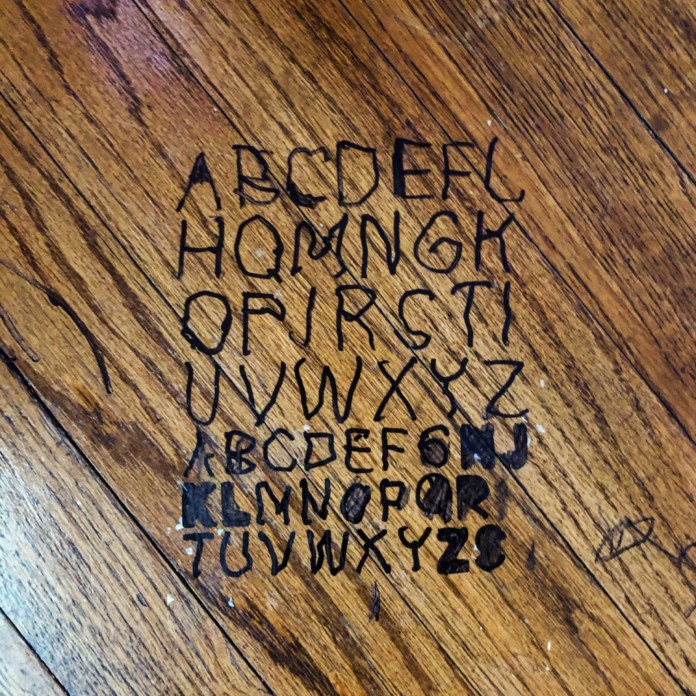

Colin drew with a Sharpie on the living room floor.

Autism Sleeps

My son sleeps,

curled under a blanket

on the couch.

His outbursts have ceased.

His cries and screams quieted.

His stimming stopped.

It’s like his autism

is in remission.

In sleep, he becomes

like any other child.

Observation After Eating Out

Pity for my son swells.

Yet I feel helpless,

Unable to intervene

To make his autism

Go away.

Our patience dwindles

As his outbursts intensify.

But love does not wane.

Instead, it grows stronger.

I have only one son.

Yes, he is different.

He is noisy and

Requires constant attention.

But I am thankful for

His presence in my life.

And who needs the quiet anyway?