In doing research for this Mother’s Day blog post honoring my late mother, Carmella DeCosty Ruane, I realize it’s the stupid shit you remember—the little, meaningless episodes that form a garland of memories. I see them wrapped around her neck like the thin, gold chain she used to wear with a small crucifix that would bounce against her breastbone when she would scurry about the house.

And why should anyone care about these memories of my mother when you have your own to cherish? I hope these specific scenes may transcend my personal history and offer a universal celebration of motherhood.

And in recalling these memories, I understand the need to forgive the flaws of my parents—to acknowledge their complex, individual personalities and to appreciate that Mom and Dad were people before becoming my parents.

Carmella DeCosty Ruane.

A Medley Featuring Mom (in no particular order)

This is the image I retain when I think about my mother:

Morning Coffee

My mother sits

in the kitchen chair

after she recites

her morning prayers.

Sunlight streams through

the lace curtains

and cigarette smoke

is suspended in the air.

She bows her small head

and presses her fingers

to the bridge of her nose,

as she contemplates

the chores for the day,

while her milky coffee cools

in a blue ceramic mug

resting within reach

on the laminate counter.

Wooden Spoon

Mom wielded a wooden spoon—the same one she used to stir sauce—to paddle our asses when we misbehaved. If Carm was upset with us and we heard the squeak of the kitchen drawer, my sister Lisa and I knew we had to hide. She would grab our arms and slap the spoon against our butts. It never hurt that bad, but it produced a nasty sound.

Twizzlers

Mom would keep a package of red Twizzlers in the car because she liked how the warmth from the sun kept the licorice soft.

Little Head

When my nephew, Paul, was about four years old and visited us from Ohio with my sister and her husband, I instructed him to repeat this phrase to Carm: “Grandma has a little head. Grandma has a little head.” Her head was small. It was so tiny that she needed to buy a little boy’s New York Yankees hat to conceal her thinning hair after receiving chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

After Treatment

In 2011, after having an endoscopy at Upstate, she reached for her cigarettes as soon as she slid into the passenger seat of my stepdad Bill’s Jeep Cherokee. Bill and I protested, saying something along the lines of, “Stop. You can’t.” She replied, “Why? Whatever’s there is there.” She died of lung cancer in November 2011.

Disciplinarian

My mother and father differed in parenting styles. Carmella was the disciplinarian, while Dad had a laissez-faire approach.

Mom instilled in us a set of immutable values; she never let us get away with anything. You never questioned adults, and if a problem arose, Carm always assumed we were at fault.

When I was about three or four years old, I remember going with Carm to visit one of her friends. The two women talked in the kitchen, drank coffee, and smoked cigarettes while I played on the floor.

Later in the visit, the host’s son, Kevin, who was about twelve at the time, came home from school and invited me up to his room to play his electric football game. If I remember the game correctly, you would set your little players on a green plastic football field and flip a switch to “activate” the game. The vibration of the game board moved the players on the field.

And I remember swiping one of the plastic players when Kevin had turned away from me or picked up the rest of the game pieces after we finished playing. I stuffed the piece in my pocket and then we went downstairs.

I sat in the backseat of our car on the way home, and I remember pulling out the game piece and playing with it. I held it on top of the front seat neck rest, to the right of my mother’s head, and I moved my hand to simulate the player’s running motion.

My mother turned her head and said, “What’s that?” I told her it was a piece from Kevin’s game.

“Did he give you that?”

“No,” I said.

“Did you take it?” she asked.

“Yes, I guess.”

Carm pulled over to the side of the road and yelled at me, saying something like, “How could you do that? You know better. We’re going back.” And she turned the car around and drove back to Kevin’s mother’s house.

She pulled into the driveway, told me to get out, and marched me to the front door. She rang the doorbell and the woman answered.

“Oh, hello again. Did you forget something?”

“No, my son needs to say something to Kevin.”

The woman yelled upstairs for Kevin to come down. He bounded down the stairs and came to the front door. I started crying, and my throat became scratchy. My mother tugged at my arm. “Go on, tell him what you have to tell him.”

I pulled out the plastic football player and said, “I took this from you. I’m sorry for stealing it.” I held up the game piece and handed it back to him.

He turned to his mother, and they exchanged glances, and then he gave the piece back to me and said, “It’s OK, you can keep it.”

I looked to my mother to see if she would disapprove. “Are you sure it’s OK?” she said.

“Yes,” Kevin said. “I have extras.”

“Well, he won’t do that again,” she said. “Now, what do you say to Kevin?”

“Thank you,” I said.

“You’re welcome,” he replied. And then we left their doorstep and walked back to the car in the gray afternoon light, a slight wind hitting my face, stinging my cheeks as my tears started to dry.

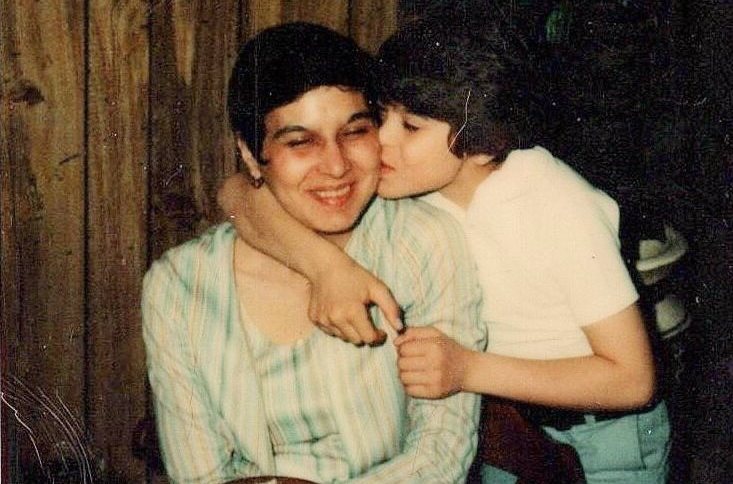

Mom, Dad, Lisa, and me.

Sunday Night Cleaning

When Lisa and I were very young, we would dread Sunday evenings because our mother would bathe us after dinner; but bathe is too kind a word to describe her actions.

Mom would make us stand, one at a time, on a step stool in front of the bathroom sink or under the showerhead in the tub while she ran scalding water on our heads. She would apply shampoo to our hair, build a lather, and then use her long, sharp nails to scrub our scalps with an intensity that bordered on cruelty. She seemed to be punishing us for having allowed dirt to gather on our skin. And we would squirm and cry as she dug her nails into our heads and tried to scrape away every flake and piece of grit. But we could never break free of her grasp; she would squeeze our arms and repeat in a sharp voice, “Stop it. Stop it.”

When she finished washing our hair, she would attack our bodies. She used an Ivory soap bar and a rough washcloth to scrub every inch of flesh, spending extra time on our ears, butts, and faces and inflicting mild pain as the cotton fabric chafed the skin. Her brisk speed of cleaning, however, meant the suffering did not last long.

After rinsing us off, she would yank us out of the tub, dry us with a towel, and maneuver our bodies as she worked our legs into pajama bottoms, pulled the tops over our heads, and slipped our arms through. Then she would march us to our rooms for bed. And on summer evenings, sunlight would filter into our rooms, and we could hear other kids playing outside, along with birds chirping and the ice cream truck making its jolly procession through the neighborhood.

I never understood what she hoped to accomplish with the vigorous Sunday cleaning. It’s not like we didn’t bathe on other days. Yet she seemed intent on trying to coat us with a sparkling shield or a veneer to repel dirt the rest of the week.

Locker Room Exposure

Before I turned six years old, I had seen several naked females up close. The viewing took place at the YMCA in my hometown of Rome, New York.

Lisa was taking swimming lessons at the Y during the winter. I was about five years old and bundled in a blue hooded parka with faux fur trim, mittens, a scarf, and heavy boots. The smell of chlorine and the visual stimuli of flesh—naked moms and daughters of varying sizes, ages, and hair color—hit me as my mother tugged at my arm and led me in a search for my sister.

Running water and the clanking of metal locker doors could be heard as girls conversed while drying off and putting on their clothes.

And then I remember one of the swim instructors standing next to my mother and chatting with her. The naked woman towered over me, and she had blond hair, a muscular body, and large breasts—a figure reminiscent of a Russian or East German Olympic swimmer.

I would later equate her image with the pictures of naked women that I would see in copies of National Geographic at the school library. By being allowed in the women’s locker room, I had entered a secret world and had gained knowledge of a habitat I did not understand but one that seemed worthy of exploration.

While my mother and the coach talked, I studied the woman’s breasts; yet the coach did not seem alarmed that a little boy was hanging out in the girl’s locker room, gazing up at her. My mom said, “This is my son, Fran.” The woman said “hello” to me in a soft voice, shook my hand, and a moment later led my mom to where Lisa was getting dressed. “Stay there,” my mother said. “I’ll be right back.”

The coach and my mom walked down a narrow corridor, passing a row of individual shower stalls with white plastic curtains hanging in front of them, while I remained behind in the middle of the room.

When my mom did not return after a few minutes, I wandered down the hallway in search of her. More time passed and I looked at the floor as I stood waiting. And then a girl in her early teens drew back a white plastic curtain and was about to step out of her shower stall when she caught a glimpse of me. When I heard her stirring, my eyes lifted from the ground, and I scanned her naked body; her still-developing breasts looked like Pillsbury cinnamon rolls.

The girl concealed her body behind the shower curtain and screamed, “Get out of here—you’re a boy.”

My mom must have heard the girl’s cry, because she came and grabbed me, squeezing my hand. She apologized to the girl—even though she couldn’t see her face—saying, “Sorry, he’s with me. We’re waiting for my daughter to get dressed.”

A short time later Lisa came out with her coat on, and we all left the locker room together. I don’t blame my mother for the embarrassing and confusing incident; it wasn’t her fault. I was a little boy, and she didn’t want to leave me behind, afraid I might get lost inside the large YMCA facility. So she felt it was necessary to drag me into the girl’s locker room with her. But even at my young age, my mother must have realized it wasn’t normal for a boy to be surrounded by naked women.

She could have offered some explanation after we left; she could have taken me aside and made a simple statement, one a child could understand, explaining the differences between male and female bodies. She could have given me some knowledge of the situation. Instead, my five-year-old brain was left to interpret the confusing images I had seen.

A holiday at my maternal grandparents’ house. Pictures are my Aunt Pat, Aunt Teresa (holding me), and Carm (in red).

Silence

Growing up Lisa and I knew that if we angered our mother, she would inflict punishment by withdrawing her affection, rejecting us with a tactical execution of the silent treatment.

She would march upstairs to her room, close the door, curl up on the bed, her soft face pressed against the pillow, and shut out the world. These episodes could stretch for days—even as she went to work and completed household chores.

Sounds took on heightened meaning. The crack of the bedroom door, the flush of the toilet, and the creak of the stairs signaled to us that she was awake and would be coming downstairs.

If she entered the kitchen to fix a cup of coffee, smoke a cigarette, or nibble on some crackers and we made the mistake of trying to talk to her, she would offer a blank expression and turn her head away. Or she would state: “I have nothing to say to you.”

My body would tighten, and I would remain quiet, unable to vocalize my emotions and say one word that could break through Mom’s stone wall of indifference.

Sometimes our misbehavior or Dad’s drinking and unhealthy attachment to his mother provoked these episodes. Other times Mom acted out for no obvious reason, but the incidents often corresponded to holidays and special occasions.

Without fail, Thanksgiving or Christmas would approach, and she would get mad about something and that would set her off.

When we were small kids, Lisa and I would sit in the upstairs hallway of our home on Stanwix Street near downtown Rome, peering at each other through the white wooden balustrades. “Do you think she’ll come to Grandma’s for dinner?” one of us would whisper to the other.

“I don’t know.”

“Go ask her.”

“No, you ask her.”

If Lisa and I told her we were going out with our father for whatever holiday it might be—informing her but not asking for permission—she would say, “I really don’t care what you do.”

She became efficient at not speaking, never giving up the silent treatment until she was ready. At some point, hours or days later, she would talk to us again. And once she resumed normal activity, she rarely apologized for her actions. It was as if the incident never happened.

Was Carm depressed? Did she have a serious chemical imbalance? We never knew.

I can’t speak for my mother, but she seemed unhappy with her life and had stayed married to Dad for as long as she could. I believe she did this for our benefit.

Here’s a poem inspired by Carmella’s silent treatment:

Aplomb

When I was a kid,

my mother’s execution of

the silent treatment

erected a scaffolding of shame.

But her rejection in my youth

produced equanimity in adulthood.

And so I thank her for the mettle

her emotional abuse constructed.

And another memory of her actions:

Family Vacation

An unhappy melody

swirls in my head,

sounds of the past,

oldies crackling

on the car radio.

A warming engine

and windshield wipers

flapping back and forth.

The luggage is loaded

and the cooler

packed with sandwiches.

Dad and the kids

are in the car,

with eyes turned

to the house,

still waiting for Mom

to open the front door

and stride across the porch.

Breakfast Encounter

When my sister Lisa was in high school, she was a serial class skipper, racking up a record number of absences at Rome Free Academy. One school day she and some friends were enjoying a mid-morning breakfast at Friendly’s when Carm and a co-worker from Rome Savings Bank walked in. Mom said she was “so embarrassed” by the encounter, but I should ask my sister what happened after Mom saw her in the restaurant. Did she scream at her? Did she walk out? Did they eat breakfast together (definitely not)?

“If It’s Meant to Be …”

Carm’s favorite expression was, “If it’s meant to be, it’s meant to be.” As a woman of faith, she left everything in God’s hands. If it was God’s will, it would happen. I hated this philosophy. It made no sense in a world torn with strife.

“If it’s meant to be, it’s meant to be” indicated to me that you could just stand back with your arms at your sides and let life come at you. But I know she used the expression as a proclamation of her trust in God.

On the Diamond

In the late 1970s, when I started Farm League, the junior league at the Rome National Little League in south Rome, I was one of the smaller players on our team—and probably in the whole league—and I remember my mother embarrassing me during one game. I was playing third base, and a runner was rounding second base and heading for third as an outfielder fired the ball to me.

The ball and the base runner arrived at about the same time, and the runner plowed into me. My hat fell off my head and my glove came off my hand. The ball skirted past me and ended up near the third base dugout. I lay spread out on the ground with a cloud of dust surrounding me, and I struggled to catch my breath. The coaches of both teams came over to me to see if I needed help. At the same time, my mother jumped out of the bleachers and rushed across the diamond. She screamed, “Honey, are you OK? Are you all right?”

“I’m fine,” I said. The coaches instructed me to sit up and then asked my mother to return to the stands. A substitute came in for me, and I sat on the bench humiliated by my mother’s actions. I didn’t want to be considered a “momma’s boy.” Later, on the way home, I told her to never do that again. She said, “I’m sorry, but I couldn’t help it. I was just so worried.”

Irritating Actions

When I would spend the night at Carm and Bill’s house on Madison Street (around 2006 to 2008), I would irritate my mother in a myriad of ways. While she was engrossed in the plot of a television program, I would swipe the remote control (undetected) and change the station or mute the sound. “Franny, cut it out,” she would say.

I would also stuff plastic hangers in her pillowcases, drawing her ire when she climbed into bed at night. “Franny, you’re so immature,” she would yell. “So immature.”

Holiday Baking

Every Christmas season, Carm would bake trays and trays of homemade Italian cookies. Her kitchen and dining room would be transformed into a factory assembly line. One time she arranged small ceramic bowls containing sugar and salt on the kitchen table. She made a pot of coffee, poured a cup, added cream, and then scooped what she thought was sugar into her mug. I witnessed her actions, and I knew she was mistaking the salt for the sugar—but I failed to intercede. And I relished the moment she tasted the coffee, her mouth curling before she spat the liquid back into her mug.

“Did you do that on purpose?” she asked.

“No,” I said. “I didn’t touch anything. I just didn’t stop you when I saw it was salt.”

“Oh, you little shit,” she said.

My family gathered at my Uncle Al and Aunt Jean’s Italian restaurant in Rome. Carm is wearing the tan suit.

Bursting Balloons

One memory from childhood illustrates my mother’s stern, humorless personality. It happened in the early 1980s when I was around twelve or thirteen years old.

Mom had just returned home after a long, hard day of work at the bank; it was early evening in the fall or winter, and darkness had fallen on our rural neighborhood in south Rome. Carm was in the kitchen getting dinner ready, as Dad would be coming home at around 6:15 or 6:30 p.m.

The previous day Dad had brought home a bunch of balloons following a home appliance sale at the Sears store where he worked. The balloons came in pink, yellow, red, and blue colors with black writing announcing the products and sale prices.

About a half dozen balloons hovered near the white textured ceiling in our basement family room. Lisa and I were watching TV while Mom was cooking upstairs. Then Lisa and I started batting around the balloons, whooping with laughter as we pranced around the room.

Mom heard us making noise, and she stomped down the stairs with her teeth gritted and a grimace plastered across her face. She rushed over to her sewing machine tucked against the wall in a corner of the room, opened one of her baskets, and grabbed a large needle. She came over to where we were playing, reached up, and proceeded to pop every single balloon.

Her intention, most likely, was to get us to shut up so she could have a few minutes of quiet before Dad came home, but her action had the opposite effect—Lisa and I laughed even louder.

I don’t remember Carm saying a word as she murdered the balloons, and when she finished her work, she returned the needle to her sewing supplies, marched back upstairs, and continued what she was doing. She did not scold us or tell us we were grounded.

And while my mother’s action seems severe, as an adult with a small child I can now relate to her need for some peace—a chance to reset oneself and decompress after working all day.

But darker forces tugged at my mother.

Mom and Dad did not offer a picture of a stable marriage, and I never experienced what one would call a normal family experience.

They separated around 1983, although they had been fighting for a long time before they decided to split; they wouldn’t divorce officially until 1990 when my mother needed an annulment to get remarried.

My parents struggled with finances, and I remember Mom working at the bank, rising early to carry out a heavy workload of household chores—cleaning the kitchen and bathroom, doing laundry, folding and ironing our clothes, making our lunches, etc. In the early morning hours or late at night, the warm glow of the hallway light would fall across the opening to my bedroom, and I would hear Mom racing around the house finishing tasks.

Even with her odd behavior, Mom never failed in her role as a mother.

And from my parents, I learned that life is hard. You work, you pay your bills, you take care of your family. That’s it. But although our childhood was rife with conflict, Mom and Dad cared for us and provided for our needs.

They dressed us in warm clothes and fed us healthy meals. They made sure we performed well in school and participated in social and recreational activities.

They took my sister to Girl Scout camping trips and me to Little League baseball games. And even though their marriage crumbled, their love for us never wavered. I think they did the best they could with the skills they were given and the conditions they faced.

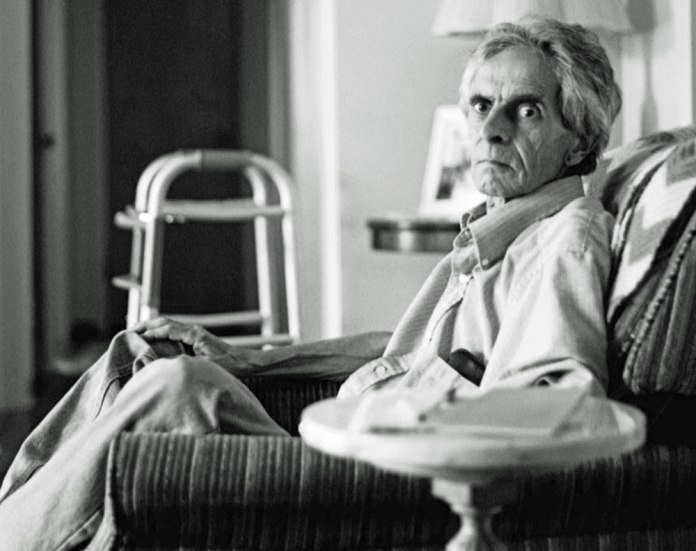

Posing with my parents prior to my surgery in 1984.

A memory of my mother after my first brain surgery in 1984:

Post-Op Image, 1984

Sprawled out on my mother’s bed,

I hear chunks of ice falling from the roof,

and a city snowplow rushing past our house.

I tilt my neck to glimpse at the wooden crucifix

perched above my mother’s head,

and feel my putting-green hair and

surgical scar meandering from ear to ear.

I then pester her with a flurry of questions,

diverting her attention from a Danielle Steel book.

She delivers no rebuke, though,

but merely clasps her nut-brown rosary beads,

and brushes them gingerly

against the disfigurement.

Comfort Objects (Previously published by The Millions)

My animosity toward musicals began in my youth when I was still in elementary school in the late 1970s. My hatred of the art form stemmed from my mother’s love of it. My mother, Carmella, never watched much television and had little interest in the arts. But whenever The Sound of Music was broadcast on television, she would claim the TV set in our house.

No matter how many times she had seen The Sound of Music, she would watch it again and again. Mom knew the words to all of the songs, and she would sit on the couch in the basement family room of our raised ranch home in Rome, a smile plastered on her face, her dark head bobbing to the music as she hummed or sang along to the tunes. Sometimes my father, Lisa, or I would humor Mom and watch the 1965 film with her; more often Mom watched it alone, drinking her coffee, smoking her cigarettes, and munching on popcorn.

But although I appreciated the talent of Julie Andrews and felt some affinity for the von Trapp family, I could never make it through a full screening of the movie. Besides being long, The Sound of Music seemed sentimental and geared toward a female audience; as a ten-year-old boy, I was more interested in watching football, baseball, Wild Kingdom, and Walt Disney specials. My interest in the musical waned after the opening sequence with Andrews prancing in a meadow and belting out the title track, with the words: “The hills are alive with the sound of music.”

If I did sit on the couch next to Mom and attempt to watch the movie with her, I would offer commentary and make fun of the action on screen. “This is so stupid,” I would say. I couldn’t understand why the characters would be talking normally one moment and then suddenly start singing. The gazebo scene with Rolfe and Liesl presents the most annoying example of this “breaking into song.”

The two meet in a park and the conversation turns to Liesl’s age. Rolfe tells Liesl, “You’re such a baby.” Liesl replies, “I’m sixteen, what’s such a baby about that?” And then Rolfe begins singing: “You wait little girl, on an empty stage, for fate to turn the light on…” Soon they are dancing inside the gazebo, their figures illuminated by a stylized lighting pattern as rain streaks the windowpanes. It seemed ridiculous to me, and my mother never explained the concept of the musical genre, the goal of telling stories and conveying emotion through dialogue, song, and dance.

Still, if Mom was watching the movie, I would try to stick around for the song “Maria” so I could sing along loudly, changing the lyrics to, “How do you solve a problem like Carmella?” Mom would become irate and order me out of the family room.

One year my father and I escaped the noise of The Sound of Music by hiding out in our mudroom, adjacent to the family room, where we played a game of Nerf basketball while Mom tried to watch her show. But even though the door was closed, we made too much noise, our bodies brushing against the drywall as one of us drove to the rim while the other tried to block the shot. Mom hopped off the couch, marched across the room, and banged on the door. “Cut it out in there,” she yelled.

I don’t know why I resented the movie so much or felt compelled to disrupt her evening’s entertainment. I should have sacrificed my time and watched the film quietly with her, trying to learn from it and appreciate what Mom saw on screen; instead, I made it difficult for her to enjoy the experience. I guess I couldn’t accept her need for the repeated viewing. I would argue with her about it.

“Mom, you’ve seen it a million times. Why do you need to see it again?” She would only say, “Because I want to. That’s all.”

I didn’t understand at the time the lure of familiar works of popular culture and the comfort they bestow. The Sound of Music touched my mother in a special way and gave her momentary pleasure. For only a few hours one night a year the film made her forget her worries about finances or her unhappy marriage to my father. I have since discovered how we often return to our favorite songs, movies, and books, seeking contentment or an escape from our daily lives.

For me it’s the 1946 film It’s a Wonderful Life, directed by Frank Capra and starring James Stewart and Donna Reed. I screen it every year during the Christmas season. I know all of the dialogue before it’s spoken, and my family gets annoyed with me over my repeated viewing. But just like Mom with The Sound of Music, I can’t stop myself from watching the saga of George Bailey’s frustrated existence in Bedford Falls—no matter how many times I have seen it before.

One of my favorite moments in the film comes when George proclaims to Mary Hatch (Reed):

“I’m shakin’ the dust of this crummy little town off my feet and I’m gonna see the world. Italy, Greece, the Parthenon, the Colosseum. Then, I’m comin’ back here to go to college and see what they know. And then I’m gonna build things. I’m gonna build airfields, I’m gonna build skyscrapers a hundred stories high, I’m gonna build bridges a mile long.”

But George never left Bedford Falls, becoming trapped by having to run the Bailey Building and Loan business after the death of his father. Growing up in the small city of Rome, tucked in the Mohawk Valley in central New York state, I could relate to George’s desire to flee the provincial setting of Bedford Falls, explore the world, and pursue his ambitions.

I recognized the same theme in Thomas Wolfe’s autobiographical, coming-of-age novel Look Homeward, Angel, as the protagonist, Eugene Gant, sought to experience life beyond the hills of Altamont, a fictionalized version of Wolfe’s hometown of Asheville, North Carolina. I carried the same urges as George and Eugene when I left Rome on a cold October morning in 1994— my used, silver hatchback loaded with my possessions—and drove southbound to Florida, where I would stay with a friend of my aunt’s and search for a job in journalism or the Sunshine State’s burgeoning film industry. I had received my master’s degree in film and video a year earlier and wanted to travel throughout the U.S. while starting my professional life.

When I was a bachelor in my twenties and thirties, It’s a Wonderful Life provided emotional succor when loneliness consumed me at Christmastime; George Bailey gave me hope that it wasn’t too late for me to fall in love—that I could find my own version of Mary Hatch, get married, and start a family. This didn’t happen until much later in my life, but the movie always lifted my spirits and helped me to withstand the hard times while I remained unattached.

And the enduring lessons about the importance of family, friendship, and faith make It’s a Wonderful Life worthy of repeated viewing. Clarence, George’s guardian angel, sums up the movie’s theme with his inscription in a copy of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer—left behind for George to read—“Dear George: Remember no man is a failure who has friends.”

After my mother remarried, and before lung cancer claimed her life in 2011, I watched The Sound of Music with her at her new home with my stepfather, Bill. My sister and I had bought Mom the DVD for Christmas or her birthday one year, sometime in the early 2000s.

I kept quiet while I sat on the couch next to Mom, glancing over at her occasionally, like when Christopher Plummer and the von Trapp family sang “Edelweiss.” Even though so much time had passed, the joy on Mom’s face resembled the delight she had exhibited when I was a child. Her face still looked the same while watching the movie, and this time I didn’t spoil her happiness.

Blurry photo from my high school graduation in 1987.

Weekend in Albany

Night—diminished faith now fights for restoration,

aided by rosary beads pressed between the gnarled fingers

of the retired Sisters of the Academy of Holy Names.

And silent petitions are mouthed

in an air-conditioned hospital chapel,

as Sister Carmella—my Aunt Theresa—

storms the gates of heaven for healing intervention,

sending out special pleas to Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

Inside the surgical Intensive Care Unit,

fluorescent lights reveal my stepfather Bill’s post-op image.

The sight of his figure catches me unprepared—

glassy eyes, belly stained with iodine,

an incision running down the sternum,

and a ventilator forcing air into his smoker’s lungs.

Mom stays close to his bed,

afraid to look away or leave the room.

Her small body trembles and

displays the effects of chemotherapy’s wrath,

evident in hollow cheeks

and in the absence of her black hair.

Unbearable heat conquers the Capital District,

and Mom finally crumbles when our used Chevy Blazer

hisses and groans and stalls along New Scotland Avenue.

She sits down on the roadside curb, dejected.

Her tears cannot be held in any longer … they gush forth

as she holds a cigarette and sips a lukewarm cup of coffee.

Almost in slow motion,

a few drops fall toward her Styrofoam cup.

I reach out to catch them,

but they slip through my outstretched fingers.

And after two days in Albany, my sister and I

must leave our mother to return home to Toledo.

On the flight back, in a plane high above

the patchwork of northwest Ohio’s farms and fields,

streaks of pink and lavender compose the sunset’s palette.

And I realize all I can do is pray;

I’m left to trust faith in this family crisis.

I ask God to hasten Bill’s recovery,

while giving Mom the strength to abide.

I lean against the window as the plane touches down in Toledo.

I close my eyes and consider if my prayers

are just wishes directed toward the clouds.

No matter, I tell myself, pray despite a lack of trust.

And so I do. I focus my thoughts on my stepfather

breathing without a ventilator and being moved out of the ICU.

Preppy Attire

After my parents separated in 1982 or 1983, when I was in junior high school, I lived with my mom and sister in our house on Lamphear Road in Rome. And although I may have been the man of the house, they outnumbered me and influenced me in many areas. I often relented to their opinions and decisions when they opposed me; together they would convince me to do what they instructed.

And I remember in junior high they dictated my style of dress for school. At the beginning of the school year, we would go shopping and Mom and Lisa would pick out for me light-blue button-down shirts, Izod polo shirts with the alligator logo, V-neck sweaters, khakis, and loafers. They were following the fashion of the times and claimed I looked handsome wearing the preppy attire. Once again, being outnumbered, I may have disliked the clothes, but I offered no resistance.

Some of my classmates dressed similarly; but they were not the popular kids who wore black leather jackets, jeans, and Rolling Stones T-shirts. But I also knew, being one of the shortest boys in the school, that I could never pull off that look.

My mother and sister’s fashion sense was rewarded because in ninth grade—my final year at Staley Junior High—I was voted the Best Dressed boy in my class. But I took my revenge on my mother and sister because I knew ahead of time the day that we were to pose for the yearbook photos for the categories of Most Popular, Best All Around, Best Dressed, and Most Likely to Succeed, etc. And on that day I wore a white Atlanta Falcons mesh practice jersey with black and red trim that my father had bought for me when we went shopping at the Champions outlet in Syracuse after an SU football game.

I was also named Most Likely to Succeed, and in both photos, I was paired with two Black girls who were considerably taller than me. In the Most Likely to Succeed picture, the girl contrasted me, as she wore a well-fitting monogrammed sweater. My two photos seem like a mistake, not only because I was grossly underdressed but also because I appeared to be a few grades younger than the girls.

But I smiled in the Most Likely to Succeed Photo, and I seemed relatively pleased with myself. I think that’s because even though I was short and not undergoing the changes of puberty, I remained popular, made the Honor Society, played on the football team, and had many friends at school. And although by ninth grade I had become concerned about my lack of growth, I didn’t view myself as abnormal.

A lot of my friends laughed and complimented me when they saw the yearbook photos. I remember one of the football players saying, “You get Best Dressed and you wear a football jersey. That’s great.”

When I showed the yearbook photos to my mother and sister, Mom shook her head and said, “Oh, Fran, you look like a real idiot.”

Keg Party

In high school, I possessed a split personality. On one hand, shyness crippled me. On the other, around my family and close friends, I sometimes overcompensated for this shyness by acting mischievous—telling jokes, playing tricks, and repeating sayings to elicit laughter—being a general ball buster and a pain in the ass. I played the fool, the clown, in a desperate bid to fit in and become popular, to distract my classmates from focusing on my differences.

One attempt to gain attention failed in a big way. In late August 1986, before the start of my senior year, my mother and Bill were set to take Lisa back to Oneonta, New York, for the start of her sophomore year at Hartwick College.

With Mom and Lisa out of the house, I decided to host an open keg party. I had never done anything this rash, but I told myself I had earned the right to have some fun. And I wanted to kick off my senior year with something that would make me stand out and boost my social clout. My risky behavior was also inspired by a scene in the teenage movie Weird Science, where Lisa tells Gary’s parents, “This guy deserves a party.” I was that guy, the nerd trying to fit in by hosting an end-of-summer kegger.

I asked my friend Todd to buy the beer. He bought a huge keg, and he and some friends dropped it off on the cement patio of my Grandma DeCosty’s old home—where Mom and I were now living—the same patio where my relatives gathered for cookouts in the summer.

It was a humid Saturday night with mosquitos buzzing and crickets chirping. But with music blaring, kids chattering, and cars driving up and down our street (with drivers struggling to find parking), the noise of the party overtook nature.

My friends and students I had never met congregated on the patio, pumping the keg, rattling the ice, and drinking beer from plastic cups. Inside the house, people were spread out in every room—some guys were in the living room watching a college football game pitting the University of Miami against South Carolina, while another group occupied a table in the basement, playing cards and smoking cigars.

Nothing in my personality suggested I would host a party of this magnitude. But people weren’t coming to the party because I was the host. They came because news spread about free beer.

I didn’t drink because I was too busy making sure everyone was behaving. Even so, the party grew out of control.

It ended due to my ineptitude. My friend Rob asked me to follow him home so he could drop off his car and then crash somewhere in my house. He didn’t want to drink and drive, and he didn’t want to leave his car on the street. So in trying to be a responsible host, I followed him home and we drove back together.

But in the intervening time, my mother called. Julie, the younger sister of one of my friends, made the mistake of answering the phone, at which point my mother heard the background noise and asked the girl what was going on. I think Julie hung up the phone without answering Carm’s question. When I arrived home, she said, “Fran, your mom called while you were gone. And I answered the phone.”

“No,” I said, tugging at my hair. “You didn’t.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know whether I should answer it or not.”

“It’s OK. Don’t worry about it.”

“She sounded upset.”

“Yeah, I bet.”

A short time later the phone rang, and Lisa was on the other end.

“Hey, what’s going on there?” Lisa asked.

“I’m having a party.”

“Well, you better get those people out of there quick. Mom and Bill are coming home now.”

“What? No.”

“Yes. Mom’s pissed. You better hurry. You have about two hours. Make sure everyone is gone and the house is clean.”

I hung up the phone, still holding the tan receiver. I remained standing in place and the blood must have drained from my face because my friends asked me what was wrong. I could barely open my mouth, but then I whispered that my mom was on her way home. I couldn’t raise my voice to scream to everyone that they had to leave, but my friend Donna stepped in and helped me. She must have recognized my desperation, and she announced the end of the party. Donna rushed from room to room and went outside on the patio and in the driveway, telling everyone they had to leave and to help clean up on the way out.

Todd or some other friends took the keg, and I grabbed garbage bags and started picking up the cups. My friend Billy and another friend, Matt, were planning to spend the night at my house. We removed all evidence of the party and wiped down every surface, and soon the house was immaculate.

We were seated on the couch in the living room, watching television, when Carm came inside. Carrying her suitcase, she walked up to the second level of the house and addressed me. “I hope you’re happy. We trusted you and you spoiled the weekend for us. You’re grounded. No car, nothing.” She then stormed up the stairs to her bedroom and slammed the door. Billy and Matt burst into laughter. “Shh. You guys are gonna get me in even more trouble,” I said.

In the morning, Matt woke me up and said he needed a ride to his job at Gillette’s grocery store, located miles away on Turin Road. I told him I couldn’t drive but offered him my old bike. And Billy and I laughed after he left the house, as we imagined John pedaling uphill along Turin Road, riding my rusty, battered bike with a rattling chain.

A day later, I remained grounded, but I begged my mother for forgiveness and wormed my way into her good graces. I told her I had wanted to do something fun, something to start our senior year on a good note. She said our next-door neighbor had complained about the noise, and she made me aware of the danger of hosting a party at her house. “You have to understand,” she explained, “God forbid someone would have gotten into an accident after drinking, I would have been responsible.”

“Yeah, you’re right,” “I’m sorry.”

“Don’t ever do it again.”

“I won’t,” I said, and we hugged.

And the story would later become a humorous anecdote I would share at family gatherings, mentioning the time I hosted a keg party and Mom and Bill raced home from Oneonta, only to find the place quiet and spotless.

One More Day

Christmas Day, the mid-1990s

As we drove along Route 365 westbound, headed for the New York State Thruway and Syracuse’s Hancock International Airport, nature’s tapestry unfolded outside the windows of the Chevy Blazer. The rolling hills of Oneida County stretched out to meet a blue-gray layer of sky, and the dark pine trees lining the highway accepted the brunt of an early winter storm.

Mom remained silent while riding in the passenger seat next to my stepfather Bill. She concealed her bald head with a red felt hat adorned with a black velvet band. A brush stroke of rouge on both cheeks and a dab of lipstick spruced up Mom’s face but could not conceal the snide grin of lung cancer underneath.

Chemotherapy had claimed most of her black hair, dyed to the roots before her illness, and her eyes seemed like black pinholes emanating a waning light. And she made no apology for her sour disposition, as she did not approve of my sister Lisa and I traveling home to Toledo, Ohio, on Christmas Day.

“What would one more day hurt?” she had asked before we left the house in nearby Rome. When we rattled off a list of obligations, she said, “Just forget I asked. It’s obvious it means nothing to either of you.”

It seemed ironic that Mom was so upset about us leaving on Christmas because our childhood experience indicated she had no fondness for holidays. Our mother spoiled numerous holidays, birthdays, and special occasions throughout the years. Before my parents separated in the 1980s, my mother loathed going to my father’s parents’ house for any family gathering.

Sometimes she would remain in her room, sleeping, crying or feigning sickness, and refusing to get in the car and go. It became our job to make up excuses when we went to our grandparents’ home without her; usually, we just said, “Mom’s not feeling very well today.” Of course, this became an overused expression.

##

Bill kept the Blazer steady on the road while Mom’s aspect—as captured in the right side-view mirror—remained expressionless.

She knew our commitments were not fabricated. We had explained long before we flew home that our stay was limited. As a corporate attorney for Toledo Edison, Lisa was due to resume her legal work in the morning, on December 26th, and I had to get back to the newsroom of News Radio 1370 WSPD, where I worked as an assignment editor and producer.

Exit 36 off the New York State Thruway took us closer to our destination. Looking out the window, I spotted flashing red lights above the horizon and heard the distant roar of commercial jet engines.

A few minutes later we pulled over to the curb in front of the US Airways terminal. Bill turned off the radio and the sound of the heater resonated inside the cramped space, but my mother’s silence felt like an indictment. Bill popped the back hatch as Lisa and I scurried outside the driver’s side door; in doing so, we allowed Mom to remain in her seat. We quickly handed off our bags to the porters stationed curbside and then turned to say goodbye to Mom.

“You kids be careful,” Bill barked out in a frosty breath. Lisa reached up to kiss him while I patted him on his back.

Mom stayed in the car with the window cracked halfway as she puffed on a Salem Light cigarette. I stepped toward the car with my sister following close behind.

“You better hurry or you’ll miss your flight,” Mom said with her eyes focused on the side-view mirror. A spire of smoke encircled her thin fingers before being snatched away by a gust of wind.

“Mom, you know we don’t mean to do this,” I said. But she failed to speak or even glance at me. I then recall either my sister or me saying something like, “We’ll be back again soon Mom,” to which my mother responded, “Why bother?”

Bill then said, “Carm, please …”

“Enough,” she said, jamming her fist into the dashboard, “just let them go.”

I reached my head inside the window and kissed my mother on the cheek. Black spots shaped like crescents stood out under her eyes, but no tears glided along the surface of her pallid cheeks. She refused to look at me, and hence, I wished to lop off—in one swift machete slice—the petty preoccupations that lurked in the land of tomorrow.

But then, as Lisa and I started to head toward the airport entrance, Mom opened the car door, shifted around in her seat, and settled her narrow frame on the curb. She approached us, wrapped her arms around me, and squeezed. She did the same to my sister, and as they hugged, Mom’s hat tipped up, revealing her bald head.

“I know you can’t stay,” she said with a sigh. She clasped my hands and added, “Go. I’ll feel exactly the same way tomorrow.”

“No you won’t,” I said.

“Yes I will. And the same goes for the day after that.”

After our final goodbyes were exchanged, my sister and I slipped past the automatic doors and into the terminal. But as we moved along the slick floor, walking in the direction of the check-in counter, I looked over my shoulder and snagged one last peek of my mom, who remained standing at the curb in front of her opened passenger door. She waved as if she had expected me to turn around, waiting to quash any lingering indecisiveness on my part.

And her accompanying smile made leaving that much easier.

##

Recalling the memory of that Christmas makes me want to be diligent to never forget her image or dismiss her behavior at the airport.

The question I ask myself is not, “had cancer changed things?” Instead, I wonder, “Why did my sister and I need a disease to come into our lives to fully appreciate our mother?”

I think it’s because for so long, my sister and I had tolerated our mother—enduring her mood swings, incessant smoking, and ruined holidays. We still loved her and needed her, but it was easier to love Mom from afar, out of her range.

Yet those were our issues. I had to look beyond the troubles of the past and see the situation from my mother’s perspective—from the vantage point of someone suffering from cancer and unsure of what the future would bring. Of course, she would be upset about her children leaving her on Christmas Day. She just wasn’t ready to let us go; like any mother, she wanted more time with her kids. And for her, time could not be trusted. It could only be measured by one more day.

Carm and Bill celebrating Bill’s birthday.

Vestiges

My parents are gone.

They walk the earth no more,

both succumbing to lung cancer,

both cremated and turned to ash.

With each passing year,

their images become more turbid in my mind,

as if their faces are shielded

by expanding gray-black clouds.

I try to retain what I remember—

my father’s deep-set, dark eyes and aquiline nose,

my mother’s small head bowed in thought or prayer

while smoking a cigarette in the kitchen.

I search for their eyes

in the constellations of the night sky.

I listen for their voices in the wind.

Is that Rite Aid plastic bag snapping in the breeze

the voice of my father whispering,

letting me know he’s still around …

somewhere … over there?

Does the squawking crow

perched in the leafless maple tree

carry the voice of my mother,

admonishing me for wearing a stained sweater?

Resorting to a dangerous habit,

I use people and objects as “stand-ins”

for my mother and father,

seeking in these replacements

some aspect of my parents’ identities.

A sloping, two-story duplex with cracked green paint

embodies the spirit of my father saddled with debt,

playing the lottery, hoping for one big payoff.

I want to climb up the porch steps and ring the doorbell,

if only to discover who resides there.

In a grocery store aisle on a Saturday night

I spot an older woman

standing in front of a row of Duncan Hines cake mixes.

With her short frame, dark hair, and glasses,

she casts a similar appearance to my mother.

She is scanning the labels,

perhaps looking for a new flavor,

maybe Apple Caramel, Red Velvet, or Lemon Supreme,

just something different to bake

as a surprise for her husband.

A feeling strikes me and

I wish to claim her as my “fill-in” mother.

I long to reach out to this stranger in the store,

fighting the compulsion

to place a hand on her shoulder

and tell her how much I miss her.

I fear that if my parents disappear

from my consciousness,

then I too will become invisible.

And the reality of a finite lifespan sets in,

as I calculate how many years I have left.

But I realize I am torturing myself

with this twisted personification game.

I must remember my parents are dead

and possess no spark of the living.

And I can no longer enslave them in my mind,

or try to resurrect them in other earthly forms.

I have to let them go.

I have to dismiss the need for physical ties,

while holding on to the memories they left behind.

And so on the night I see the woman

in the grocery store aisle,

I do not speak to her,

and she does not notice me lurking nearby.

But as I walk away from her,

I cannot resist the impulse to turn around

and look at her one last time—

just to make sure

my mother’s “double” is still standing there.

I want her to lift her head and smile at me,

but she never diverts her eyes

from the boxes of cake mixes lining the shelf.