Today marks the forty-first anniversary of my first brain surgery. As I’ve written about before, on Dec. 12, 1984, when I was fifteen years old and a sophomore in high school, surgeons at SUNY Upstate Medical Center (now named Upstate University Hospital) in Syracuse, New York, removed a large craniopharyngioma that had engulfed my pituitary gland, leading to stunted growth and delayed puberty. Since then, I’ve had four additional surgeries and two Gamma Knife radiosurgery treatments at Upstate.

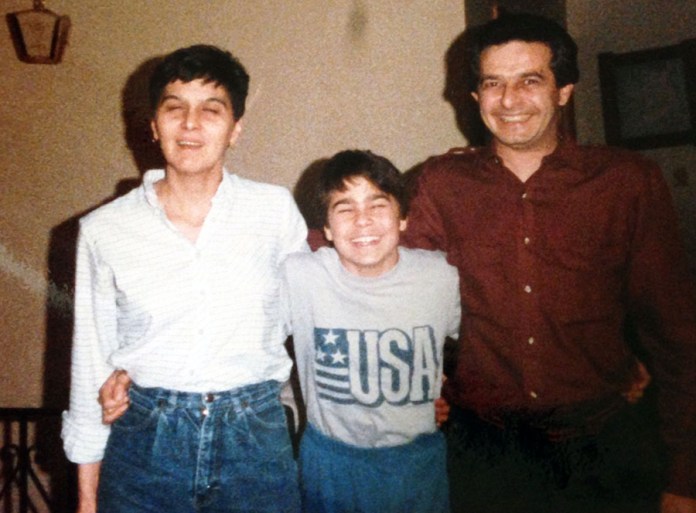

Posing with my parents prior to my surgery in 1984.

Prior to the initial surgery, in the fall of 1984, a scan of my head had revealed a cloudy mass in the sella region at the base of the skull, and the results of a follow-up CT scan with radiation contrast came a few weeks later.

I received the news about the brain tumor diagnosis from my father when he picked me up from wrestling practice on a cold November night. This essay describes that encounter.

Craniopharyngioma

##

After I put on my black wool pea coat, pulled a knit hat down around my ears, and slung my book bag over my shoulders, I pushed open the back door of the gym and walked outside to meet my father, who had parked behind the high school.

The cold air hit my face and stung my gloveless hands as I strode toward the car; a floodlight cast a large net of bright, white light on the pavement. Dad drove up, and I got in.

He left the car idling, and as I slid into the passenger seat and adjusted myself, he leaned over and kissed me on the cheek, his tan winter coat brushing against the steering wheel. I felt a trace of his beard stubble against my skin, and I could smell a faint odor of Aqua Velva or Brut combined with cigarette smoke. The heater hummed, and he lowered the blast of air and turned and looked at me. I wondered why we weren’t moving yet. He wasn’t crying, but he appeared on the verge of spilling emotions.

“What’s the matter, Dad?” I asked.

“Upstate called your mother today,” he said. He switched on the overhead light, reached into his jacket pocket, and pulled out a torn piece of paper. “Here,” he said, handing me the slip of paper, “this is what they think you have. I wrote it down, but I don’t think I spelled it right.”

In a slashing style in faint, blue ink, my father had scribbled a misspelling of the word craniopharyngioma. His voice cracked as he said, “It’s cranio-phah-reng . . . something like that . . . oh, I don’t know. It’s some kind of brain tumor.”

I looked at the paper as my father let out a sigh. He shook his head and said, “I prayed to God when you were born that this wouldn’t happen to you, that you wouldn’t have to go through the same thing I did.” His words referred to his health crisis as a teenager, one that caused small stature and delayed puberty and led to ridicule by his classmates.

Francis DiClemente Sr. was born with a hole in his heart, a ventricular septal defect. On June 12, 1959, when he was sixteen years old, pioneering cardiac surgeon C. Walton Lillehei performed open-heart surgery on him at the University of Minnesota Hospital, successfully repairing the defect.

The heart problem disrupted Dad’s high school years, and he faced a long recovery; but he rebounded after the surgery, lifting weights to become stronger and adding muscle to his thin frame. He grew to his final adult height, graduated high school from St. Aloysius Academy in Rome, and went to work at the city’s Sears Roebuck store.

After sharing the information with me, he pressed his lips together and shook his head again, and he seemed locked in position in the driver’s seat, unable to contend with the news, incapable of going through the motions of driving away. We clenched hands, and I said, “It’s OK, Dad. Don’t worry. But what do we do now? What’s next?”

“You have to go back there for more tests. You may need surgery.”

“All right,” I said. “It’s OK.”

“I hope so,” he said. “All we can do is pray.”

He switched off the overhead light, put the car in drive, and drove out of the parking lot. We grew silent as we passed the naked trees lining Pine Street in our city of Rome, New York.. We crossed the intersection at James Street and made our way toward Black River Boulevard.

While my father was anxious and crestfallen, I felt elated as I gripped my book bag in the passenger seat. The CT scan with contrast had confirmed my suspicions, indicating a grave medical condition was responsible for my growth failure at age fifteen, offering a reason why my body had not changed, why I had not progressed through puberty, and why I remained so different from the other boys my age. I still considered myself a physical anomaly, but the tumor proved it wasn’t my fault.

I looked down at the piece of paper again and studied the word. Craniopharyngioma. I tried to sound it out in my head while my dad steered the vehicle, and I thought the word would twirl off my tongue like poetry if I rolled down the window and yelled it. Craniopharyngioma. Cranio-Phar-Ryng-Ee-Oh-Mah. It reminded me of onomatopoeia, which I had learned about in my tenth-grade English class.

##

And here are two related poems:

Case History

Stricken with pituitary insufficiency,

I felt my way through

a stage of delayed puberty.

When adolescence took hold for other kids,

I remained like a boy wrapped in toddler’s clothes.

My face looks older now,

and my body has grown.

But I could not escape

the endocrine impact of that cranial intrusion.

For even though benign,

the tissue overtook me,

and in effect, the tumor

scarred my life and altered my future.

Craniopharyngioma (Youthful Diary Entry)

Craniopharyngioma gave me

an excuse for being unattractive.

I had a problem inside my head.

It wasn’t my fault

I stood four foot eight inches tall

and looked like I was

twelve years old instead of eighteen—

and then nineteen

instead of twenty-four.

I couldn’t be blamed for

my sans-testosterone body

straddling the line

between male and female.

The brain tumor

spurred questions

about my appearance,

aroused ridicule,

and provoked sympathy.

I heard voices whispering:

“Guess how old that guy is?”

And, “Is that a dude or a chick?”

And while I waited for my

body to mature, to fall in line,

and to achieve normal progression,

I remember wishing the surgeons

had left the scalpel

inside my skull

before they closed me up,

knitting the stitches

from ear to ear.

I prayed the scalpel

would twist and twirl

while I slept at night—

carving my brain

like a jack-o’-lantern—

splitting the left and right

hemispheres,

and effacing the memory

of my existence.