My mother passed away from lung cancer thirteen years ago today. It’s hard to believe she’s been gone that long. When Carmella died, I was recovering from transsphenoidal brain surgery (through the nose) and couldn’t attend her wake or funeral mass. The surgeons instructed me to avoid blowing my nose for at least eight weeks, and I was concerned about getting emotional at the services and springing a cerebral spinal fluid leak.

Carmella DeCosty Ruane.

These days, I think about Carm when washing the dishes she gave me or ruminating about how she would have loved spoiling my son, Colin.

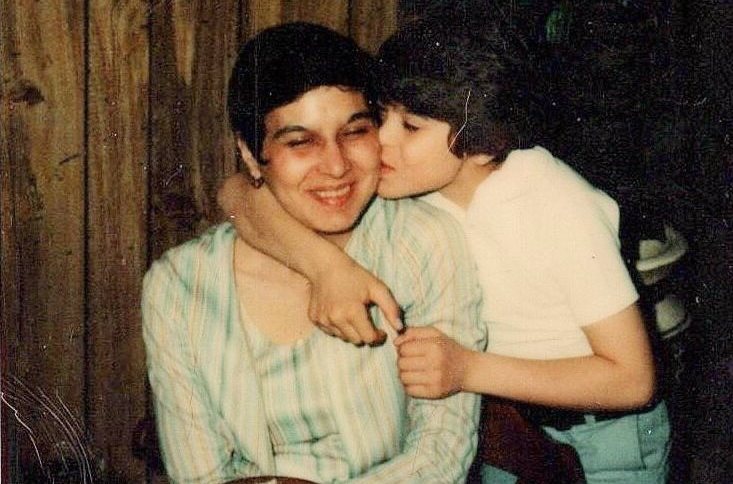

My parents and my sister, Lisa, kissing me.

Here are two poems that capture the memory and spirit of my mother.

Morning Coffee

My mother sits

in the kitchen chair

after she recites

her morning prayers.

Sunlight streams through

the lace curtains

and cigarette smoke

is suspended in the air.

She bows her small head

and presses her fingers

to the bridge of her nose,

as she contemplates

the chores for the day,

while her milky coffee cools

in a blue ceramic mug

resting within reach

on the laminate counter.

Vestiges

My parents are gone.

They walk the earth no more,

both succumbing to lung cancer,

both cremated and turned to ash.

With each passing year,

their images become more turbid in my mind,

as if their faces are shielded

by expanding gray-black clouds.

I try to retain what I remember—

my father’s deep-set, dark eyes and aquiline nose,

my mother’s small head bowed in thought or prayer

while smoking a cigarette in the kitchen.

I search for their eyes

in the constellations of the night sky.

I listen for their voices in the wind.

Is that plastic bag snapping in the breeze

the voice of my father whispering,

letting me know he’s still around …

somewhere … over there?

Does the squawking crow

perched in the leafless maple tree

carry the voice of my mother,

admonishing me for wearing a stained sweater?

Resorting to a dangerous habit,

I use people and objects as “stand-ins”

for my mother and father,

seeking in these replacements

some aspect of my parents’ identities.

A sloping, two-story duplex with cracked green paint

embodies the spirit of my father saddled with debt,

playing the lottery, hoping for one big payoff.

I want to climb up the porch steps and ring the doorbell,

if only to discover who resides there.

In a grocery store aisle on a Saturday night

I spot an older woman

standing in front of a row of Duncan Hines cake mixes.

With her short frame, dark hair, and glasses,

she casts a similar appearance to my mother.

She is scanning the labels,

perhaps looking for a new flavor,

maybe Apple Caramel, Red Velvet, or Lemon Supreme,

just something different to bake

as a surprise for her husband.

A feeling strikes me and

I wish to claim her as my “fill-in” mother.

I long to reach out to this stranger in the store,

fighting the compulsion

to place a hand on her shoulder

and tell her how much I miss her.

I fear that if my parents disappear

from my consciousness,

then I too will become invisible.

And the reality of a finite lifespan sets in,

as I calculate how many years I have left.

But I realize I am torturing myself

with this twisted personification game.

I must remember my parents are dead

and possess no spark of the living.

And I can no longer enslave them in my mind,

or try to resurrect them in other earthly forms.

I have to let them go.

I have to dismiss the need for physical ties,

while holding on to the memories they left behind.

And so on the night I see the woman

in the grocery store aisle,

I do not speak to her,

and she does not notice me lurking nearby.

But as I walk away from her,

I cannot resist the impulse to turn around

and look at her one last time—

just to make sure

my mother’s “double” is still standing there.

I want her to lift her head and smile at me,

but she never diverts her eyes

from the boxes of cake mixes lining the shelf.

A beautiful tribute. Heart wrenching

Thank you for reading it, Yassy.

Thank you.